Selling Your Soul, Or, Can One Just Take Out a Mortgage?

“In Celtic wisdom we remember that our soul, the very heart of our being, is sacred. What is deepest in us is of God.”

~John Philip Newell1

What is Soul?

Short answer, I don’t know.

I don’t have any religious schooling or certificates in spiritual formation or any of that. I’m just reflecting here because I need to develop a deeper understanding of and relationship to my own soul. That’s all to say, take what you read here with a grain of your own salt. It’s just one person’s perspective as of today.

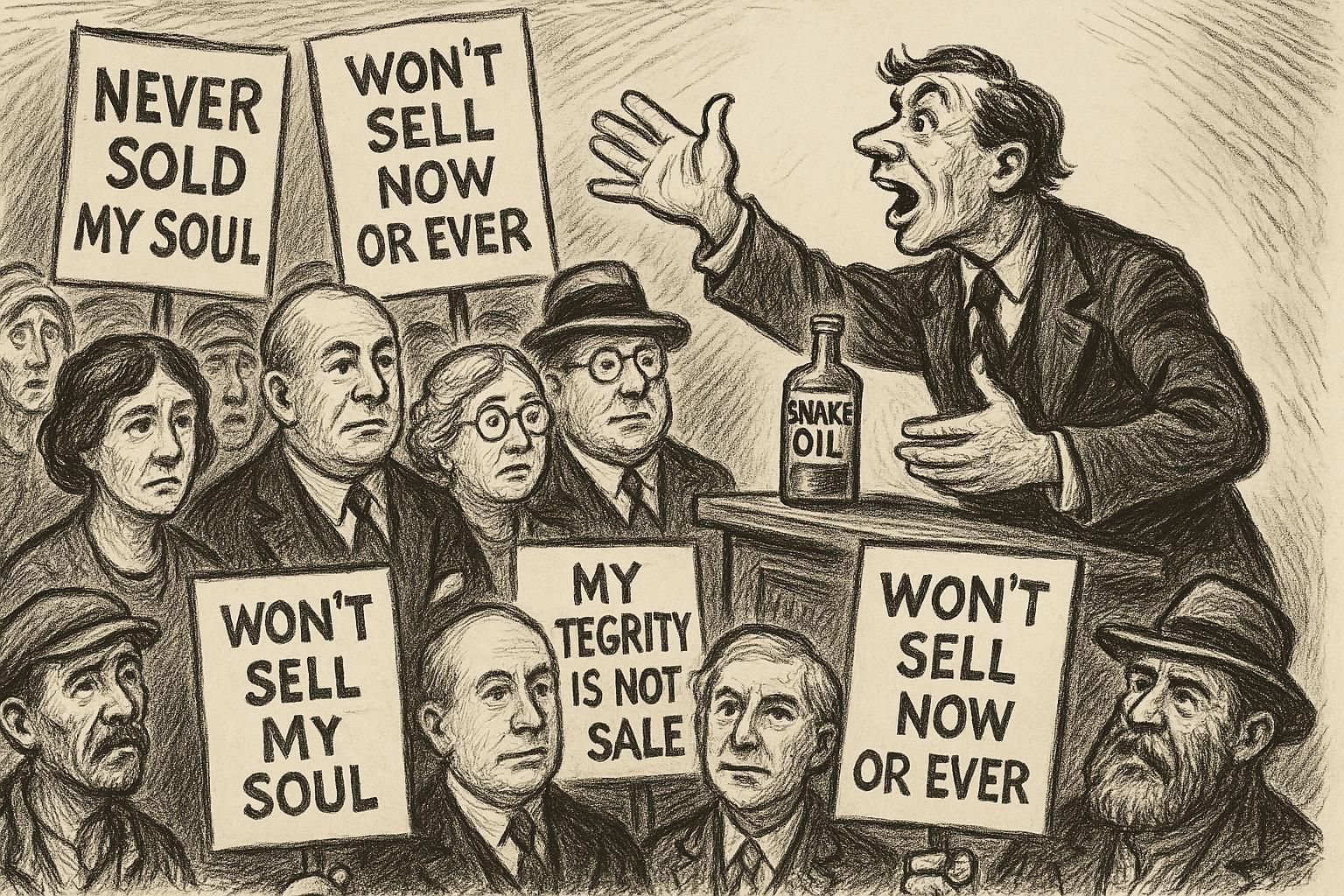

Saying “I don’t know,” therefore, isn’t all that surprising, but isn’t this something we all ought to be thinking about? Shouldn’t we all be doing our best to be true to the depths of who we are, to what is most meaningful to us, especially in the midst of the shallows and the shadows all around us?

Is one’s soul enough of an entity, do you suppose, that one might “sell it” in exchange for something perceived as worthwhile like, say, eternal life or great power, wealth, or pleasure? Or, closer to home, to receive by hook or crook the promotion someone else deserved? Or to win the game nefariously? Or to deviously win a bet on the game? Or to browbeat someone into saying they agree with you when you know they don’t?

¿Quién sabe?

Je ne sais pas.

I dinna ken.

I don’t know.

And nobody else does either. Not even the saints, not even the mystics, and not even your minister or favorite doctrine can express it accurately and completely. Not for sure. Not for good. Folks can try to explain the territory, and they can track down the horse, and they can name that horse, but can they even capture the magnificence of that horse? Can they tame that horse? Can they break that horse? Some have tried mightily and even poetically and dutifully and helpfully to encapsulate what that horse represents. Some have even tried to hobble it, but…

….it’s a bit of a mystery, you see.

Long answer, a lot of very wise people have tried to lasso a definition for soul and to pull it in. But it’s like roping a pooka. The rope of reason can never pull it in. One can think and think and think and, more importantly and usefully, to experience and experience and experience, and still not be able to say exactly what it is. One can’t corral it, to continue the metaphor, or herd it. One can only hop on as best one can, if we can, and take a ride wherever it takes you. One can “become one with the horse of our soul.”

Enough horsing around. Let’s get down to it.

The word ‘soul’ has always been an ambiguous word for me, and it’s no surprise given all the ways people have tried to explain it. Emily Dickinson wrote, “I cannot see my soul but know “tis there.”2 Phil Cousineau, who wrote my go-to book about pilgrimage,3 also edited a book dedicated to exploring soul.4 The readings in this book are written by a wide range of thought leaders ranging “from Socrates to Ray Charles.” No surprise, the spiritual, unexplainable yet universally experienced “soul” has also been addressed by the great religious traditions as well as deep ponderers over the centuries. Cousineau includes essays, poetry, and lyrics from Plato, Rumi, Black Elk, May Sarton, Jack Kerouac, Alice Walker, and many more. So many of these differing approaches, the many ways of explaining soul, are playing similar chords. Cousineau’s Prologue, I think, is a worthy read for anyone wanting to move toward a deeper understanding of soul.

In the Prologue, Cousineau says, “To fathom the unfathomable soul we immediately plunge into mystery. To probe the images of the soul as the vital force, the source of consciousness, the persistence of things, the core of individuality, the depth dimension, the raw, blue rhythm of life, is to suddenly, with Lear, ‘take upon us the mystery of things, as if we were God’s spies.” 5 He continues,

If we’re not bewildered by the mysteries of the soul, we’re not thinking clearly, to paraphrase the scrawling on subway walls. For the soul’s mysteries compress the most profound mythic questions that have always intrigued human beings. Where do we come from? Why are we here? Where do we go when we die?6

“Every known culture,” he says, “has taken upon itself the naming of this force, usually after words for wind, shadow, movement, smoke, strength.”7 The meaning and experience of soul defies a taut, concrete, complete interpretation. Words – which are reductionist symbols to start with - attempt to define soul, but the soul cannot be fully expressed using them. Yet we sense soul, we count on it to be the essence of who we are. “For many,” Cousineau says, “soul is the constellating image for the paradox of unchanging depths in an ever-changing universe.”8

To summarize, soul can never be completely defined. It represents the deepest essence of who we are, each of us, though we be in the midst of doom scrolling, trolling, extolling, logrolling, button-holing, or universal attention-spoiling. Though we be the least soulful-seeming people one might find watching a reality show or checking out celebrity “how to stay young” tips. Even when we be surface-skimmers, each of us has the capacity to resonate with who we are underneath all that makeup, barroom bluster, or manly Big Truck-covered-with-tough-sounding-stickers-and-big-flags. Even when we be whiners about how our fancy dinner or “Best Burger in the World” wasn’t quite as tasty as usual. Even when we be starry-eyed woke, or we’re not and just don’t get it, sitting asleep at the wheel. The soul, for any of us and all of us, resides.

The beatitude, one might say, abides.

Even at our most superficial, each of us is endowed with something much deeper than we often experience. Cousineau provides the rejoinder to the superficiality which can engulf us:

Down deep in your soul where infinity is echoing. Deep down where the backbeat of eternity resounds, the deep bass line underneath the melody of all things. Soul, nothing but infinity closing in, constantly.

I am haunted by soul.9

Haunted. Deep. Infinity. Eternity resounds. “The deep bass line underneath the melody of all things.” Whoosh. He pretty much proves me wrong, doesn’t he, in being able to describe qualities of soul. What soul is. Unhobble that magnificent horse. Take a ride on that deep bass line that reverberates deeper than woke, deeper than populism, deeper than any “isms” or national borders. It’s an existential beat.

Best answer, we sense what soul is when we experience connection – perhaps sense some kind of resonance - with our deepest self. We can sense it in others who live their lives in generative, purposeful, wise, joyful ways. We sense it when our deepest deep is aligned, harmonizes, with the divine. With God.

Importantly, we can intentionally become more aware of, develop, and act in ways that are congruent with our deepest sense of soul. Never completely integrated – we are human and fallible after all, but increasingly. It’s a lifetime journey.

We tap into our souls through music – some music is even called soul music, but we can experience soul through opera, folk music, lullabies, hymns, chants, and the other musical genres. Just as the experience of mountain top awe or turbulent ocean waves can crack our social facades wide open, reaching inside us to pull forth the most authenticness of us – exposing the hidden soul, and blooming it to ourselves and maybe even the world – so can music. As can wrenching loss. As can astonishing art. As can a sprouting flower. As can tragic loss or a miraculous cure. As can barely moving a toe just as the gurney pulls up after being thrown to the ground by a 350-pound defensive tackle. As can seeing your daughter being born or your son marching into the hall to Anchors Aweigh at the end of bootcamp. It’s more than pride, more than happiness, more than sadness, it’s all that but at their most essential. It’s the absolute core of who we are. It’s the most profoundly meaningful to us and of us.

Our soul is with us always, though we gloss over it, though we know it not.

Though we seem to abandon it.

The Soul Can Become Lost but Never Sold (Well…perhaps…)

I thought and spoke much of the soul. I knew many learned words for her. I had judged her and turned her into a scientific object. I did not consider that my soul cannot be the subject of my judgment and knowledge; much more are my judgment and knowledge the objects of my soul. Therefore the spirit of the depths forced me to speak to my soul, to call upon her as living and self-existing being. I had to become aware that I had lost my soul.

~Carl Jung, The Red Book10

One of my favorite movies, based on the play, is A Man for All Seasons,11 Here we find Sir Thomas More, who gave up the power and the prestige and the safety bestowed by King Henry XIII because he would not sign the Oath of Supremacy, which would acknowledge the King as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. More, deeply Catholic, refused to sign the document and thus was accused of treason, resigned his position as the Lord Chancellor of England, was sent to the Tower of London, was eventually convicted, and then beheaded.

This is a story about how one man plumbed the depths of his soul and found it too precious, too fundamental to the pith of who he was, and lost his life for it; and of another man, who betrayed him for a bauble.

The play contrasted More with Richard Rich, a man More once mentored. More’s strategy to avoid being found guilty of treason was to remain silent about the Oath, to not take a position on it. This meant that, according to law, he could not be convicted. The strategy seemed like it might work until Rich falsely testified that More had confided in him that the King was not the rightful head of the church. Thus, More’s fate was sealed.

In the play, More notices that Rich has been rewarded with the title of Attorney General for Wales, presumably for his false testimony. And then gives one of the most withering remonstrations in all of literature.

'Why, Richard, it profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world... but for Wales?'12

This indictment, spoken softly and directly, follows the words of Jesus, in Mark 8:36:

For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? (KJV).

The next line in the Bible is verse 37:

Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul

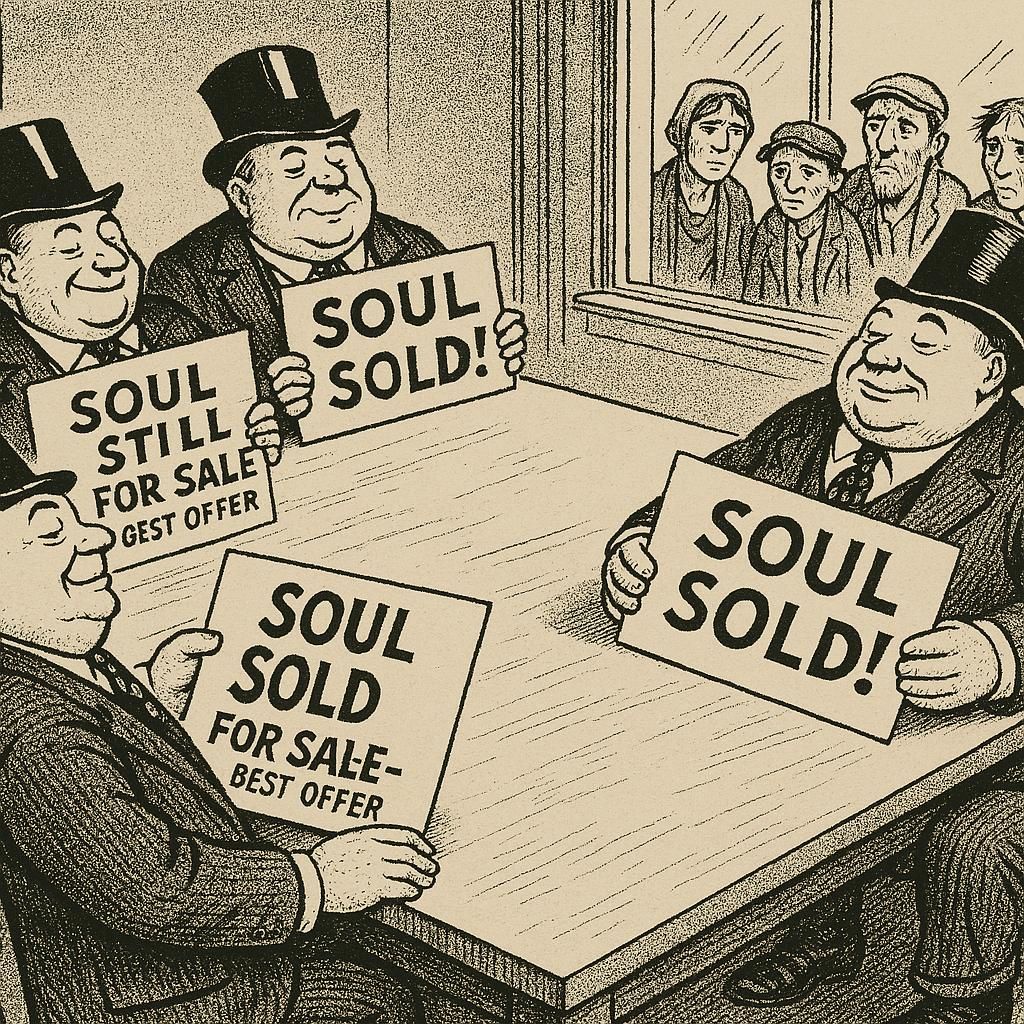

What, indeed, shall a person give his or her soul for? For selling your influence and power as a Senator in exchange for bribes and gold? For the huge wealth and recognition that comes from being a top TV show opinion star? For not being primaried in your otherwise safe district?

For becoming the Attorney General of Wales?

There are, of course, mistakes made by us all, some of which are just poor decisions, others are family or loved ones preservation decisions, some are just downright mistakes so wrong that they couldn’t be considered mistakes as much as intentional acts of malice or greed.

But even if Jesus used the terms, “losing one’s soul” and “exchange one’s soul,” can one actually give up their soul, and if they were able to, what would remain? Does forfeiting one’s principles and values, whether in exchange for something directly given or through inaction when virtuous action is called for – sins of commission or omission - constitutes the absence of soul?

Losing and exchanging – not selling

From Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – Faust (1808)13

“That I to the moment might say: ‘Stay, thou art so fair!’ Then bind me in thy bonds, O time and fate, and let my soul be sold.”

This in Faust, his soul in exchange for knowledge and pleasure.

From Howard Roark, speaking in Ayn Rand’s, The Fountainhead14,

"To sell your soul is the easiest thing in the world. That's what everybody does every hour of his life. If I asked you to keep your soul—would you understand why that's much harder?"

These two very different, deep thinkers from different eras, Goethe and Rand, are talking about the trade offs – between easy and hard, and present happiness in exchange for – one can assume – eternal hell. And once one’s soul has been “sold” that that’s it. Game over. Very, very hard to keep it in the first place.

With due respect, my view is that we might lose our soul – as in “lose sight of,” “can’t find,” “abandon,” “trade it off for baseball cards,” but that it can almost always be found again, a year from now or on our deathbeds. We might mortgage our soul – take out a loan on our soul which we’ll be paying for until we pay it back through, say, good deeds. Which we might never do, but which we can do. But to sell it? Nah. We (N.B. the possible exceptions in the next paragraph) will always have our soul.

Are some people irredeemable? So evil that they can never retrieve their souls from the Lost and Found? Those are God’s Grace questions. I’m idealistic enough to think that everyone can be ultimately loved and forgiven. I’m realistic enough to think that some people really have sold, not just mortgaged, their souls. And that some people are “born” to be ‘soul less”? No matter their environment.

I’m not smart enough to know the answer to those big questions. But I’m convinced that most of us have the opportunity become more soulful. That is, full of soul.

I have thought a lot about what it takes to sell our souls – please see below a poem I wrote in 2019 – or even if a person can do that. Isn’t the soul always a part of us, even if we ignore it, even lose sight of it in the midst of everything else that is bludgeoning our sense right and wrong? I think the portal to the soul is opened through our practices which strength virtue in our lives, our sense of humanity, our love for nature, and all the gifts we have been given, unearned.

The most complete answer might be, “How can I be, and continue to become, a better person?”

We know what a better person would be, instinctively, because we do have soul as a deep reservoir inside us, just waiting for us to jump in and drink.

“How can I be, and continue to become, a better person?” It’s a question I ask myself often, and I think it’s the never-ending quest for all of our lives.

Notes

1Newell, J. P. (2021). Sacred Earth, sacred soul: Celtic wisdom for reawakening to what our souls know and healing the world (First edition. ed.). Harper One. p. 23

2Dickinson, Emily. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, Little, Brown and Company, 1960. Poem 1101.

3 Cousineau, P. (2021). The art of pilgrimage: the seeker's guide to making travel sacred. Conari Press. (2012)

4Cousineau, P. (1994). Soul: An Archeology. Harper.

5Cousineau, P. (1994). Prologue. Harper, p. xix

6Cousineau, P. (1994). Prologue. Harper, p. xix

7Cousineau, P. (1994). Prologue. Harper, p. xix

8Cousineau, P. (1994). Prologue. Harper, p. xxi

9Cousineau, P. (1994). Prologue. Harper, p. xxxiii

10Jung, C. G. (2009). The red book: Liber novus (S. Shamdasani, Ed. 1st ed.). W.W. Norton & Co, pp. 128-129

11Bolt, Robert. A Man for All Seasons: A Play in Two Acts. London: Heinemann, 1960. Also adapted by Bolt for the screen in A Man for All Seasons, directed by Fred Zinnemann, Columbia Pictures, 1966, starring Paul Scofield, Wendy Hiller, and Robert Shaw.

12Bolt, R. (1960). A man for all seasons: A play in two acts (p. 91). Heinemann. Also adapted by Bolt for the screen in Zinnemann, F. (Director). (1966). A man for all seasons [Film]. Columbia Pictures.

13Goethe, J. W. von. (2000). Faust: Part I (P. Wayne, Trans., p. 59). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1808)

14Rand, A. (1943). The Fountainhead (p. 577). Bobbs-Merrill.

“My friends, it is wise to nourish the soul, otherwise you will breed dragons and devils in your heart”

~C. Jung, The Red Book, p. 130)