From 100,000 To 1

Carol Rogers-Shaw • June 5, 2020

There is something profound about reducing 100,000 to 1, yet knowing still that your own 1 is replicated in other stories of other people’s 1.

Photo of Irene C. Mulligan Rogers taken by Carol Rogers-Shaw

"As she handed the phone back to the nurse, I heard her start to cry. I heard her say she missed us. I was alone with my dog, walking through the neighborhood, and I couldn’t stop sobbing."

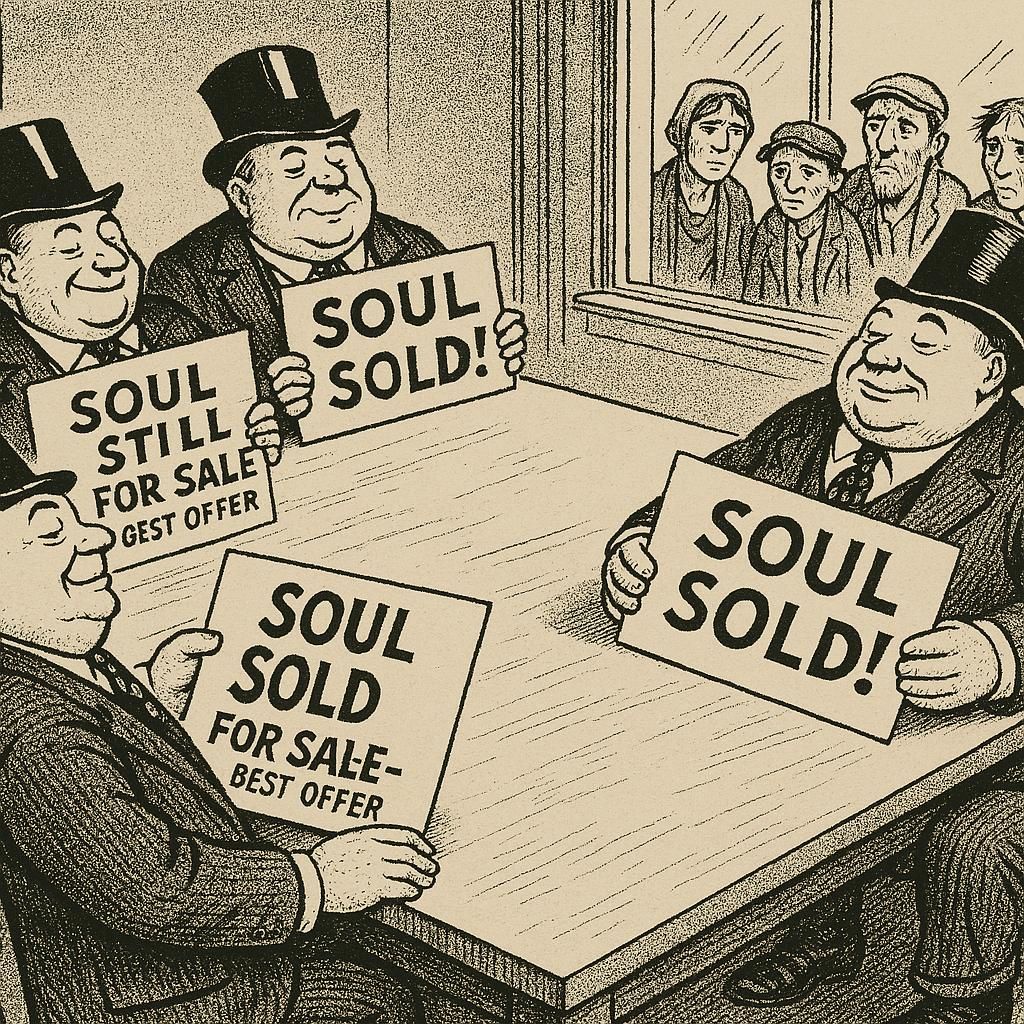

Billy Collins was the U.S. poet laureate when the 9/11 attacks took place. He wrote a poem to honor the victims. It is called "The Names" in honor of the victims, their loved ones, and the survivors. He goes through the alphabet, seeing the names of the victims in the natural world, in raindrops, on flower petals, on tree branches (https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/poet-billy-collins-reflects-on-9-11-victims-in-the-names). The last line of the poem is “So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.” There were 2,977 victims of 9/11. Already there are over 100,000 Americans who have died from covid-19. How can we even begin to fathom what that number is like?

In schools around the country, elementary students celebrate 100 Day by bringing in 100 pennies, or paper clips, or Cheerios. What would 100,000 pennies or paper clips or Cheerios look like? The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has a collection of 4,000 shoes representing only a small fraction of the victims of the Holocaust. What number would we choose to represent the victims of covid-19? What item would we collect?

On May 24, 2020, the New York Times chose the number 1,000 and created a front page listing the names and excerpts from obituaries and death notices of people who have lost their lives. The assistant editor said she wanted to “represent the number in a way that conveyed both the vastness and the variety of lives lost” (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/reader-center/coronavirus-new-york-times-front-page.html). According to local news sources, two teenagers in Durham, North Carolina then took 100 of those printed front pages and posted them to the Free Expression Bridge at Duke University, providing another stark visual of the loss. They “were struck by the power and simplicity of the newspaper front page and wanted to show their community what 100,000 names looks like” (https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article243002481.html).

When we face something that is difficult to understand, these visual models can help put things in perspective, but when we start to understand what those numbers mean, how can we find room in our heart to honor and remember, especially as the deaths from the pandemic are continuing to mount? I concentrate on the individuals, the names of the individuals on that front page, the people I know who have been ill or died.

On April 24, 2020, I defended my dissertation entitled Performing Disability: An Autoethnography of Persevering and Becoming. In one section discussing disability in the time of a pandemic I had included the following passage:

My mother is in a nursing home, and no visitors are allowed. Even if they were, because of my compromised immune system, it would be impossible for me to visit. I wake up from nightmares that she will die alone. She’s not physically ill at the moment, but I can’t help thinking that our shelter-in-place will last so long that her death will come. She has dementia, and although I want her to know me when we talk on the phone, I almost wish she would lose more of her understanding of what’s happening. The other day the nurse dialed my phone number for her. I told her about my daughters working from home, we talked about the weather, and I explained I couldn’t visit until the virus was gone. I told her to ask the nurse to call me every time she wants to talk. I’m not sure she understood. We said good-bye. As she handed the phone back to the nurse, I heard her start to cry. I heard her say she missed us. I was alone with my dog, walking through the neighborhood, and I couldn’t stop sobbing.

When she first fell ill a few years ago and needed full-time care, I had to clean out her apartment. As I went through things she had saved, I cherished great memories, until I opened the bottom drawer of her dresser. Inside was a fairly new bathing suit. My mother loved going to the beach. Every summer we would take the long drive to Jones Beach in New York, drag the beach chairs, toys, umbrella, and cooler to the water’s edge. After a long day in the sun, swimming in the waves, building sand castles, eating tuna sandwiches, nectarines, and brownies, we would make the long hot sandy ride home. We took vacations to the shore, and we spent days digging for clams at Sherwood Island State Park. As I sat on the floor in my mother’s empty apartment, I cried because I knew she would never feel the sand beneath her feet or smell the ocean’s salt water or float on the undulating waves. My mother is a wonderfully kind and caring person whose love for our family has always been a clear, bright, warm presence in my life. And she was strong; she faced adversity and she kept on going. Now, as my tears fall on the keyboard, I only hope she will keep on going until the pandemic ends, and I can hug her again before she dies.

The next day, April 25th, I received a call from the nursing home; my mother had tested positive for covid-19. My mother is still alive, she’s still in the covid wing of her nursing home, and she still tests positive for the virus. I can’t visit her, hold her hand, or give her a hug. I can schedule a video phone call every couple of days. The aide holds the iPad screen in front of her, and I talk. Her dementia has intensified, so although she recognizes me, she doesn’t understand that she can talk to me. She tells the aide I am her daughter. She asks the aide if I’m at the nursing home. She stares at my image as I tell her about our family. I tell her I love her, and I’ll visit her when the virus is over. Sometimes she says good-bye, and as I hang up the phone, I hope it’s not the last time. For people who have lost someone they love, the only number that counts is the one they lost. There is something profound about reducing 100,000 to 1, yet knowing still that your own 1 is replicated in other stories of other people’s 1. Shared loss doesn’t ease the pain, but it makes you part of a community, even if it’s one you wish did not include you.