Herman Hesse and the (Later) Seasons of the Soul

“I got interested in aging, as I like to say, when aging got interested in me.”

~ Terry Sanford, in the Foreword to Reflections on Aging and Spiritual Growth, p. 15

Alone

You can travel many roads

And so many trails all over the world,

But remember all paths

Lead to the same finish.

You can ride, you can drive

In twos or threes,

But you must take

the last step alone.

No schooling, no skill

Will suffice or save you

From having to face

Each grave challenge alone.

Herman Hesse, Alone

Hesse and Fischer, The Seasons of Soul, 2011, p. 110

Herman Hesse, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946, is well known and lauded for his novels, such as Siddhartha and The Glass Bead Game. He also, come to find out, wrote poetry. Andrew Harvey, in the introduction to Hesse’s collection of 68 poems, The Seasons of The Soul, maintains that it is in his poetry where:

“. . . you meet most intimately Hesse the man in all his emotional intensity, sometimes scalding self-knowledge, and fierce spiritual struggle, and so experience most completely the inner turmoil and revelations that led to his becoming one of the philosopher-sages of our tumultuous transition” (p. ix).

It might be tempting to write off Hesse’s work as that of an earlier era, he died in 1962, but that would be a mistake. Ludwig Max Fischer, translator, curator, and commentator for The Seasons of the Soul, writes that Hesse, who became popular in the United States during the turmoil of the 1960’s and 1970’s:

“ . . . was food for the heart, balm for the soul, and light for the spirit. A young generation was rebelling against authoritarian structures and the destruction of ideals by unlimited greed, political power plays, and bourgeois complacency. Hesse served as a beacon of authenticity, a trustworthy guide, and a fearless explorer on the perennial paths taken by pilgrims of the inner journey” (p. xiii).

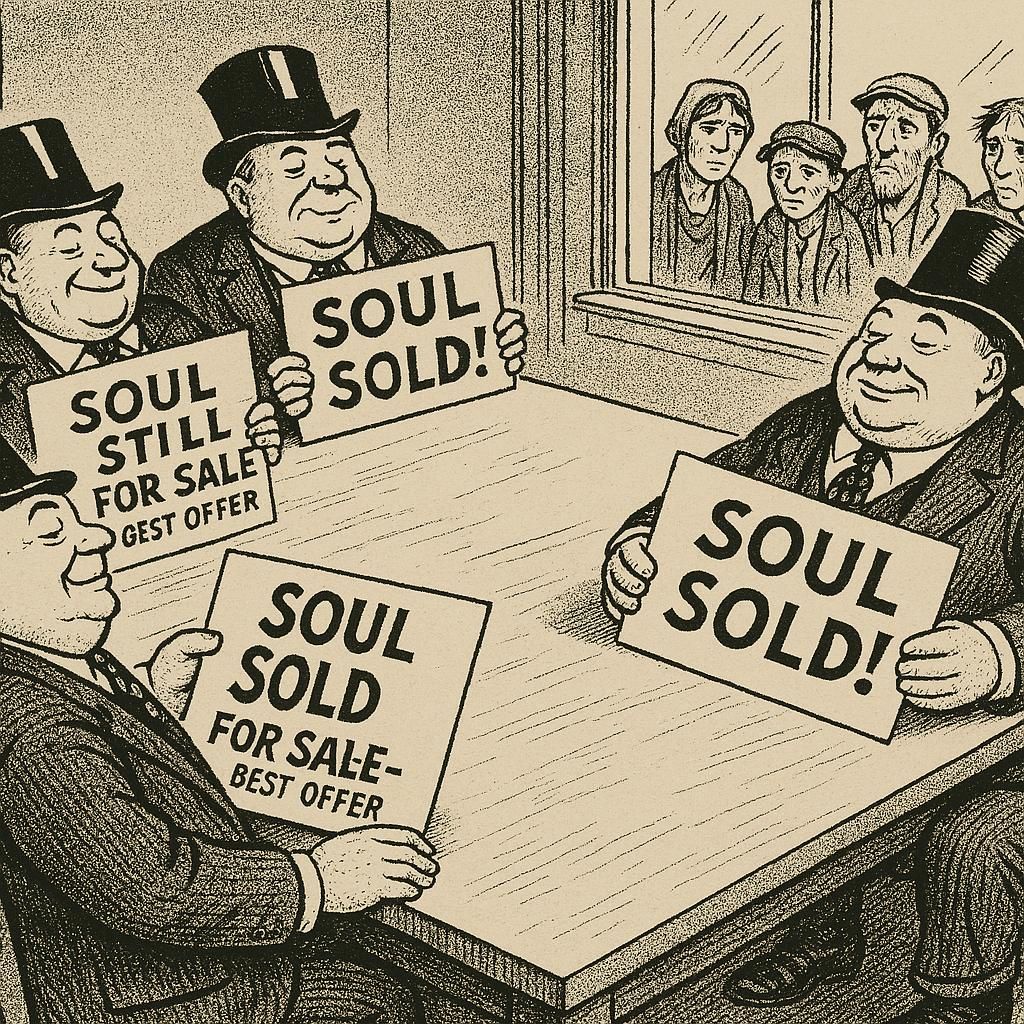

We have a different ‘young generation” these days. They and we (the formerly young generation, now the generation of elders), could use – in fact, I think we desperately need - more such beacons of authenticity just now; more light showing a path through darkness rife with intentional inauthenticity, Machiavellian plotting, unremorseful prevarication, and deliberate dismantle-ification of democratic values of integrity and honesty.

Truth, justice, the American Way (yeah, I grew up on Superman), and good ‘ole plain local, neighborly goodness still permeate the U.S.A., but we’d be fools not to recognize the current threat to freedom, democracy, and the way of life that has been the envy of the world.

Poetry - whether it be Dante’s epic three-canticle, 100-canto journey to hell and back or simply one of Boshō’s keen, spare haikus, precious as a Ruby Roman grape - uses the essential to represent the existential. It requires just the right words, carefully selected and artistically assembled. And a reader open, sensitive, and resonant.

Poetry is an agile way to plunge into the depths of wisdom, and The Seasons of the Soul is a tiny pool, abyssally deep. It is comprised of sixty-eight poems Hesse wrote over sixty-four years. The section I dove into, The Seasons of Life and the Passage of Time, contains sixteen poems, with titles like Dreaming of Paradise, It Is Too Late Now, Growing Old, and Stages. Why this section? At seventy-one years, I exemplify Terry Sanford’s thought, “I got interested in aging, as I like to say, when aging got interested in me.” I’m interested in learning what I can about aging and in particular, the ways that nourish and flourish mind, body, heart, and soul.

I reckon that means learning about the tough truths as well as the easy ones. It is helpful to know we are alone; but then again, we aren't really, are we? It's helpful to know about death, it's inevitable, right? But knowing about death can give us a much deeper respect for and richer experience of life.

In Alone, Hesse reminds us that nothing comes between us and our final destination. No matter how much valuable support we receive or don’t receive, ultimately death looks into our eyes. It is ours to face alone. “You can ride, you can drive/In twos or threes,/But you must take the last step alone,” he writes. If death looks into our eyes, we can also, I think, look back into death’s eyes. “Death is always with us, in the marrow of every passing moment,” as Zen Hospice cofounder Frank Ostaseski says in The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully. Death “is not waiting for us at the end of a long road,” he says, but is our secret teacher, helping us “to discover what matters most.”

“Death is much more than a medical event,” he says, “It is a time of growth, a process of transformation. Death opens us to the deepest dimensions of our humanity. Death awakens presence, an intimacy with ourselves and all that is alive.”

Believe me, I'm not looking for death, but it's true that I've been thinking quite a bit about it lately, after spending most of my life just trying to avoid thinking about it. My mistake, but it's not too late for me, I don't think. Acknowledging that my time of life grows shorter and shorter has focused my attention on not missing what I have left and to do what I can to live it as fully and healthily (body, mind, relationships, soul) as I can manage. I don't do that well, yet. But you know, step-by-step.

The Pilgrim begins,

I was always on a journey,

I was always a pilgrim,

I have kept little for myself,

all bliss and pain are behind me.

p. 106

This five stanza poem takes the reader on the pilgrim’s journey, “A thousand times I must have stumbled,” he writes, and finishes with:

The bright and brilliant world

I had grown to love is leaving.

I never found the pot of gold,

but I know this: my journey was brave.

Sometimes I think my journey was brave – after all, just getting through a day requires courage – sometimes I don’t think it was so at all. Certainly there have been plenty times when it wasn't. Getting older, the opportunity is to look back on an ever-growing lifetime of experiences, decisions, and outcomes of those decisions, can be rich reflection but only if we do not dwell in the past, or even live in the past. Monica Furlong, in a reflection titled A Spirituality of Aging, found in the edited book, Reflections on Aging and Spiritual Growth, emphasizes the opportunity we have to live life fully now, regardless of age. “What I believe can redeem old age, as indeed the whole of life,” she says, “is a passionate commitment to living as fully as possible, whatever the restrictions; to enjoying whatever there is to be enjoyed; to laughing at whatever is there to be laughed at. Intensity is what matters” (p. 49).

Hesse, in Growing Old, writes,

If you can still smile, you will be young,

will still stand strong,

pursue your passions with power,

and bend with forceful fists

the poles of the world together.

p. 104

Laughing at myself, perhaps too often, perhaps even too disingenuously too often less authentically than need be, remains a joy. Laughing at the ludicrousness, silliness, pratfalledness, and irreverence of folks who take themselves way too seriously (here is where I include myself oft-times), is just a cleansing mechanism. It reminds me that I'm a pebble on the beach.

And I can smile at beauty as well. Beauty of spirit, beauty of nature, beauty of word and deed. And with these smiles come tears of course, as well. Irreverence pierces our smug hypocrisy; beauty pierces our heart. When young, it is easy, said Hesse, "but when our heartbeat starts to stumble/a smile becomes a conscious task." As long as it is a conscious task, it seems to me, it's something we can probably manage to do, now and again. And again.

Henri Nouwen and Walter Gaffney didn't write poetry in their book, Aging: The Fulfillment of Life, but - just a good - used pictures. Pictures of old people. Old people living, loving, hugging, working, caring for others, smiling - and, oh yes, laughing out loud. They also get to the nitty-gritty, the essence, and I'll close with this from them.

"We believe that aging is the most common human experience which overarches the human community as a rainbow of promises. It is an experience so profoundly human that it breaks through the artificial boundaries between childhood and adulthood, and between adulthood and old age. It is so filled with promises that it can lead us to discover more and more of life’s treasures. We believe that aging is not a reason for despair but a basis for hope, not a slow decaying but a gradual maturing, not a fate to be undergone but a chance to be embraced” (pp. 19-20).

Hesse, like Nouwen, Gaffney, Furlong, Ostaseski, and so many others in so many ways, captures the poetic soul of aging.

Sources/Resources

Furlong, M. (1998). A Spirituality of Aging? In A. J. Weaver, H. G. Koenig, & P. C. Roe (Eds.), Reflections on Aging and Spiritual Growth (pp. 43-49). Abingdon Press.

Hesse, H., & Fischer, L. M. (2011). The seasons of the soul: the poetic guidance and spiritual wisdom of Hermann Hesse (L. M. Fischer, Trans.). North Atlantic Books.

Nouwen, H. J. M., & Gaffney, W. J. (1990). Aging (First Image ed.). Doubleday.

Ostaseski, F. (2017). The five invitations: discovering what death can teach us about living fully (First edition. ed.). Flatiron Books.

Sanford, T. (1998). Foreword. In A. J. Weaver, H. G. Koenig, & P. C. Roe (Eds.), Reflections on Aging and Spiritual Growth (pp. 15-16). Abingdon Press.