How about resolving to develop your inner life this year?

The inner life is where our deepest struggles, hopes, awareness, virtues, and understandings occur.

“Men (sic) to-day are so overwhelmingly occupied with objective tasks; they are so busy with the field of outer action, that it is a particularly opportune time to speak of the interior world where the issues of life are settled and the tissues of destiny are woven.”

Rufus Jones, The Inner Life, 1917

On the Camino de Santiago, September 1, 2022

Photo Credit: Shane Kroth

How about resolving to develop some aspect of your inner life this year?

I remember distinctly the afternoon I was having a couple of beers with two close friends. This was a few years ago. We were sitting outside 10 Barrels here in Boise. I’d been around these two fellas, both great guys, often over time, and between the two of them we had traveled together, written together, biked together, had many mutual friends, had created many stories together, spent hours over beer and coffee and – well, we were and are friends. They were shocked when I told them that I was deeply depressed and anxious and had been for a long time. The key words here are, “for a long time” because they told me that they’d had no idea.

Apparently, I had been good at hiding it. You know how it’s done; you’ve done it. Acting like there’s not a care in the world while inside you are in turmoil. Putting on the mask. (That’s called, BTW, ‘emotional labor’.) It’s exhausting, right?

"How's it goin'?"

"Great!" (If you only knew...)

There are a lot of ways I could go with this essay from here, one of them being that your friends and others can’t help you if you don’t let them in on what is going on with you. No matter how much they care about you and would want to help you, if you won’t share your troubles with them, they just can’t.

Another way would be to talk about my path to what I believe now to be a pretty robust and hearty mental health today. It always needs buttressing and growth and contemplation, but I’m buoyed by friends, family, religion, work, and so many other parts and pieces of life that I am grateful for and which enrich each day. The older I become, the more abundant I feel my life becomes along the way.

Still another way, which this essay is about, is to start to explore this “inner life”, as Rufus Jones and others call it. Jones, in his 1917 book, The Inner Life, said “Men (sic) to-day are so overwhelmingly occupied with objective tasks; they are so busy with the field of outer action, that it is a particularly opportune time to speak of the interior world where the issues of life are settled and the tissues of destiny are woven” (p. ix).

Over a hundred years later, it seems still an opportune time to pay attention to this “interior world".

The Habits

Reading Stephen Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change was transformational for me. It has sold over 40 million copies since it was first published in 1989 and continues to be a best-selling book, decades after I read it for the first time. What Covey did so well was an earlier version of what Malcomb Gladwell does so well. He took challenging topics, often based on research or ideas which had been around a long time, and made them easier to understand and remember through stories and examples and simple visual figures, and showed how we could apply them to our day-to-day lives.

I became a certified Seven Habits trainer for our company (and other Covey-certified courses as well), and teaching those courses not only was a joy but also deepened my knowledge and my life.

These days, after Covey’s stunning success, it isn’t hard to find others who have written about the “Six Principles of This,” the “Five Rules of That,” or the “Twenty-one Essential Practices for This or That.”

Still, the original Seven Habits is timeless. The habits Covey shares are easy to understand, but like most habits, they aren’t easy fixes. They’ll take a lifetime of attention and yet never be fully mastered. Covey himself wrote, “I personally struggle with much of what I have shared in this book. But the struggle is worthwhile and fulfilling. It gives meaning to my life and enables me to love, to serve, and to try again” (p. 319). The confession I made to my buddies that day at 10 Barrels came years after I’d read and led The Seven Habits courses.

I had backslud.

Big Time.

It's a lifetime pursuit, this.

Foundational to The Seven Habits is the idea of working on ourselves from the “inside-out”. As Covey writes, “’Inside-out’ means to start first with self; even more fundamentally, to start with the most inside part of self—with your paradigms, your character, and your motives” (pp. 42-43).

This beginning point comes from recognizing that true and lasting personal transformation starts with oneself, and by then building and maintaining healthy, generative disciplines, practices, habits, and routines to intentionally change our own lives – not just in what we do, but in who we are – over time. Elementally, this means developing a deep, meaningful inner life.

Developing the Inner Life

Covey was not the first, of course, to talk about developing the innermost parts of ourselves. Rufus Jones, for example, speaking in The Inner Life, said “The deepest issues turn, not upon the choice of ‘things,’ but upon the choice of the kind of self that is to be, and the most decisive dramas are those that are enacted in the inner world before our private theater” (p. 5). Jones thought the outer and inner life were both important parts of religious life (he was a prominent Quaker of his time), but that people are “overwhelmingly occupied with the field of outer action” (p. ix).

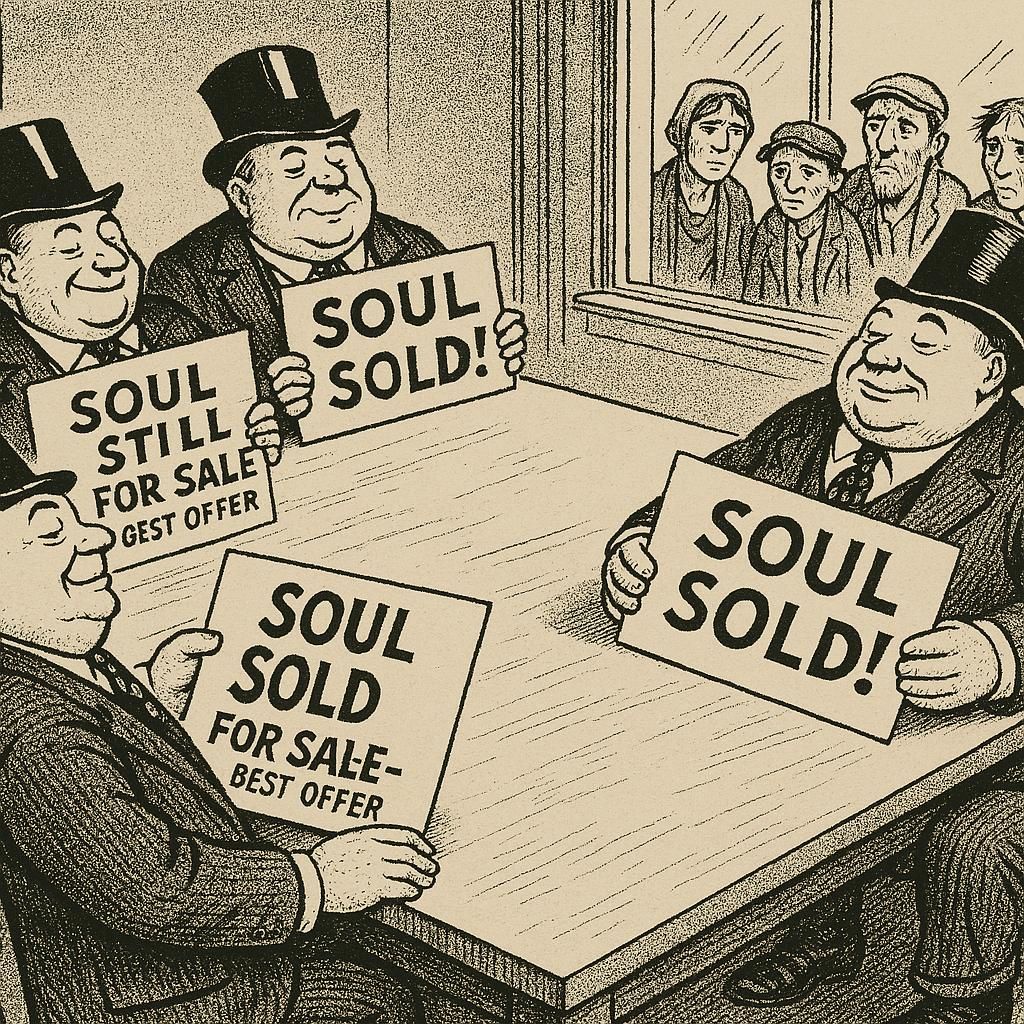

Both the inner life AND the outer life are important and iteratively influence each other. Lots of us just don’t spend as much time working inside ourselves as we do outside themselves. We seek attention and ascension and mentions, with cardinal values intentions in absentia.

In the best case, working on the outside means focusing on one’s long-term physical health, building material assets, family life, and career and life markers of value. A worser case, giving primacy to the outside of ourselves, would be living a life primarily around immediate rewards – food, drink, entertainment, pleasure, celebrity, adulation – at the expense of longer-term prosperity. In other words, giving in to immediate gratification most of the time at the cost of building riches of the most important kinds - long term health, wealth, relationships - via delayed gratification. The worst case, well, it would be the worstest, wouldn’t it?

The inner life might be considered as levels of centeredness. Noncentered people, Fr. Richard Rohr says, are difficult to live with. They have to defend “their reputation, their needs, their nation, their security, their religion, even their ball team.” You might be one of these people if you are, he says, “hurt or offended a lot. You can hardly hurt saints,” he says, “because they are living at the center and do not need to protect the circumference of feelings or needs” (pp. 25-26).

Rohr, a Catholic priest, breaks with contemporary views of the polarity between conservative and progressive, writing that “centered people are profoundly conservative, knowing that they stand on the shoulders of their ancestors and the Perennial Tradition. Yet true contemplatives are paradoxically risk-takers and reformists, precisely because they have no private agendas, jobs, or securities to maintain” (Rohr, Everything Belongs, p. 24). Is it crazy to think that a person can be both conservative and progressive?

I don’t think it’s crazy at all.

That’s one way I would describe myself and hope the description is at least fairly accurate.

In fact, I think it’s who we all really are the deeper we go. Labels do not capture the fullness of who we are.

One aspect of the inner life is the depth of our knowledge and our ability and effort to think and learn and reflect. Another aspect of the inner life is our moral being, our character, and our values. Still another aspect of our inner being is our heart, and the depth of our love and care for ourselves, others, and all creation. Being deep-hearted with others starts from within, from that great gratitude and love we nurture and feel, to selfless generosity overflowing from us to others.

At our deepest levels, when we move deep into the well which feeds our center – call it God or spirit or just the spark of life or the sources of who-we-are – we are much, much more than simply a Democrat, a Republican, a Russian, an American, a Catholic, a Protestant, a Buddhist, a youth, an elder, an employee, or any other label we or others might use. Religion, at its best, is a vehicle for developing the spiritual life. It certainly has been and continues to be for me. Politics, at its best, serves to deepen discourse and to develop substantive courses of action for governments and societies, and to inform our individual perspectives about our role in the body politic and as citizens of our nations and the world.

At deeper levels, we bridge and integrate those humanly constructed labels, those artificial constraints. That is because the inner life is bottomless – there is always a deeper place to go. There is always something we do not know or have never ever heard of or considered. There is always a more profound sense of awe we have not yet experienced. There is always mystery we have not yet, nor in our lifetimes ever will, fully fathom.

At the center of the center, even mind, heart, knowledge, and identity are subsumed by the awareness of being totally present. Some would say at the deepest level – or perhaps in the most present moment - all of these qualities just drop away. Depth psychologist David Benner says that “the search for meaning is really a search for presence, because grand systems of truth or meaning can never satisfy the basic human longing for life to be meaningful. Without presence, nothing is meaningful. But in the luminous glow of presence, all of life becomes saturated with significance” (p. xiii).

What is this relationship between the deepening of our inner life and experiencing complete physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual presence in the moment? Total presence does not depend on thought, knowledge, or even deep feelings at all; and the deepest, most meaningful wisdom might never result in the epiphanal, total presence of a moment. I do think, however, that one can lead to the other iteratively, recursively. I’ll need to think more about that and I’m curious to learn more about this relationship.

All of this is getting too deep for me for now. To paraphrase Will Parker (“Kansas City”, in the musical Oklahoma), I’ve gone about as fur as I can go.

How about an Inner Life Resolution?

The inner life is where our deepest struggles, hopes, awareness, virtues, and understandings occur. It is where both our beliefs and our uncertainties lie. It is where our quest for truth and meaning and being continues or comes to a stop sign. The outer life – how we act and react and take in the world - is the manifestation of our inner life. The inner life - how we develop, or don't develop, our spiritual, moral, emotional, thoughtful qualities - is the source of how we undertake the journey of our outer life. The longer I felt I had to shield my inner self from the world – to hold that mask tight – the harder it was for me. I had to let as much of it as possible go, to share my vulnerabilities, to be able to work on them.

How meaningful might an inner life resolution this year be for you, your family and friends and relationships, the world, and beyond?

Sources/Resources

Benner, D. G. (2014). Presence and encounter: the sacramental possibilities of everyday life. Brazos Press.

Covey, S. R. (1990). The seven habits of highly effective people: restoring the character ethic (1st Fireside ed.). Fireside Book.

Jones, R. M. (2013). The Inner LIfe. HardPress Publishing. (1917, Originally published by The McMillan Company)

Rohr, R. (1999). Everything belongs: the gift of contemplative prayer. Crossroad Pub. Co.