Profound Thinking

Michael Kroth • December 26, 2019

What have you found to be helpful to think more deeply over time?

The Central Doctrine of Science:

All Properties and events in the physical universe are governed by laws,

and those laws hold true at every time and place in the universe. (p. 97)

I call the Central Doctrine of Science a doctrine because,

despite its success, it cannot be proved.

It must be accepted as a matter of faith.

No matter how lawful and logical the material cosmos has been up to now,

we cannot be sure that something illogical, unexplainable,

and fundamentally unlawful might happen tomorrow. (p. 99).

~Alan Lightman, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine

Although each of us have many questions in life, such as “Will I get a raise next year?” (Or…”Will I have a job next year?), many of the most important questions become “truths” for us over time, and therefore are unquestioned unless those truths become problematized.

Take singing. Once, in the thrall of a young woman (actually, this was junior high, such a tender age), I sang to her over the phone. I remember “Strangers in the Night” but, really, it might have been anything popular in the day. I sang to her over the phone. Whoosh. Sit on that a second. Junior high boy. Singing to a girl.

She laughed at me.

I don’t remember the details. They are lost in the trauma of time. What I do remember is that from that day on I did not sing for others. My assumption, based on that one piece of data, was that I had a lousy voice. Couldn’t sing.

So, rather, than embarrassing myself again, I didn’t. Sing for others that is. For years. Until I tried out for a swing choir in college, and a kind choral director named John Clark gave me a chance. After that, though I never became a very good singer, I loved singing and even performed in musicals – my favorite of all art forms – and am not afraid to sing loud and unembarrassed in church or wherever the God of Singing strikes me.

One off-hand comment by a junior high girl created a “truth” in my head that modified my behavior or years. It took an act of hope to try out for that swing choir, and an act of faith – I believe – for someone to give me a chance, for that “truth” to be discovered false.

Beliefs, though we consider them to be truths, are at best partial truths. They are, for those who are courageous and inquisitive enough to go deeper, just way stations on our pilgrimage toward – but never completely reaching – the whole truth. If you did have the whole truth you would have to be God or Dr. Omniscient, and if so I would like to meet you. The divine is infinitely more mysterious and even the natural world is infinitely more unknowable than I can imagine ever completely understanding, feeling, or experiencing. (For more on this, see Beliefs Are Resting Places On Our Journey

and Is Your Heart Right?" And/Or "What Do You Believe?)

Even scientists, whose profession is dedicated to questioning current beliefs about truth, mayn't question their own Big Assumption about truth, that there are natural, unchanging, dependable laws. This is Lightman’s “Central Doctrine of Science”, which opened this essay. Even scientists who treat this as a working assumption, one needed to undertake their work, often forget that this “doctrine” is, like the beliefs of every religion, an article of faith.

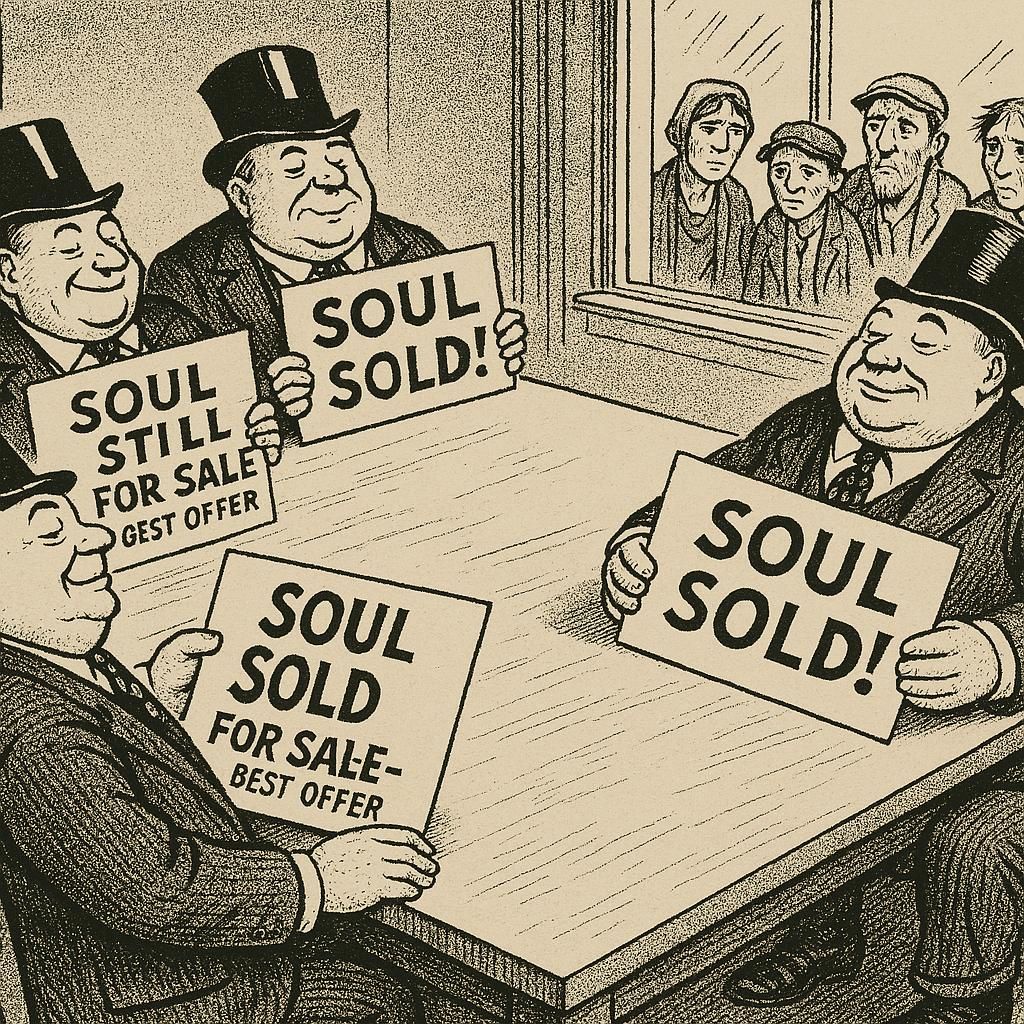

Ergo, hardly anyone is immune from the security of belief. Beliefs, as I have discussed elsewhere, are both practical (we use them every day) and impractical. Remember the old joke about assumptions? They make an “ass” of “u” and “me”. And, if we aren’t in the habit of testing and questioning those assumptions (which are also known as ‘beliefs’ and take the form of often-very-opinionated opinions), we might never consider that someone would have the audacity to fly planes into buildings.

Strategic planning for our governments and for our lives is all about questioning assumptions and then acting on potential alternatives. We skip that step at our peril.

Profound thinking, like all aspects of profound learning and living, is grounded in practices. Therefore, we all have access to profound thinking and we all can become more profound thinkers over time. If we have the discipline to practice, that is.

This is a big and important topic in our exploration of profundity, which we will return to often. Here, I just list a few practices of profound thinking to get us started. Again, anyone can pursue these and can become better at them. It does not require an Einsteinian brain.

Some Processes of Profound Thinking

Imagining:

Throwing caution to the winds and letting your mind wander. It’s no surprise that science fiction writers, through active imaginations, anticipate – perhaps even make possible – actual scientific progress.

Creating:

Having the courage to make something completely different, to develop whole new genres (of music, for one, art for another, car designs still one more), by taking imagination and making something concrete out of it.

Elaborating and Nuancing:

Recognizing that whatever your brain conceptualizes now is just a smidgeon of what there is, and working to develop more – more historical information and perspective, more ways to conceptualize, more possibilities, more, more, more. What we studied in high school is just the surface of knowledge. Same with gardening. Same with crafts. Same with politics, and religion, and philosophy, and, well, anything we can think about.

Combinatory Play:

OK, OK, Einstein did excel in this – coined the term, actually (for more, check out this Brain Pickings essay

– but that doesn’t mean we have to be geniuses to practice it. As Maria Popova described it in this article:

“For as long as I can remember — and certainly long before I had the term for it — I’ve believed that creativity is combinatorial: Alive and awake to the world, we amass a collection of cross-disciplinary building blocks — knowledge, memories, bits of information, sparks of inspiration, and other existing ideas — that we then combine and recombine, mostly unconsciously, into something “new.”

Combinatory Play – developing and then combining and recombining cross-disciplinary building blocks – then, is something we can all practice. Go play!

Immersing: Want to think more deeply? Immerse yourself. In a different culture. Language (especially a new language). Folks to hang around with (especially those much different than yourself). In a hobby (hobbies, like all good practices are wonderful because there is no end to them – you can never be done with them, never be at a place where you can’t work to become better). Jump in!

Bracketing Assumptions:

The trick here is to become aware that you operate almost totally on assumptions about what you believe to be true. I assume people will stop at red lights. I assume I’ll live another 30 years. I assume my religion is the one true religion. I assume that climate change is real (or is a a hoax). Our behavior for the most part (we do, after all, have reflexes and such), is based on these assumptions, each of which has more or less validity. Profound thinkers can bracket, or step outside those assumptions – put them on temporary hold – to test them, to look at new or different perspectives, to improve or deepen or modify or discard them. This is a practice.

Cruciblizing/Containerizing:

This is developing a place physical or mental where your deep understandings, ones you have built over years, by trial and error, can be mingled with other ideas, practices, beliefs, and rituals in order to become richer and more substantive. In science, this is having deep knowledge of one’s discipline so one can confidently and creatively and expertly look at and incorporate other disciplines. In religion, it is being secure enough in one’s own faith tradition to confidently interact with and learn from other faith traditions. The strong container allows for this mix, this crucible for thinking, and can enrich understandings and practices, and allow beliefs to continue to evolve and deepen.

Strategic Thinking:

Strategic thinking can involve any number of the above practices – bracketing assumptions (could anyone fly over the Maginot Line?), imagining different possibilities (what if the economy were to take a serious fall in 2008?), and so on. Sherlock Holmes famously was a deducer, but was also an inductive and abductive thinker. There is also scenario planning, looking at probabilities, and on and on.

These are practices…we can learn them. Each of us.

These are ones I have been thinking about, but there are more (comparing and contrasting comes to mind as I write). What have you found to be helpful to think more deeply over time?