Silence Is Not Soundlessness

Jennie Lake Trail

Jennie

Lake Trail

is located north of Idaho City, Idaho. It is about four and a half miles long and is rated "difficult". I convinced my friend Vince (AKA Vinji) that I might be able to make the trek. He is a regular and experienced hiker but for me this hike out-and-back would be about twice as far as I normally walk each day and has an elevation gain to the lake of almost 2000 feet. He graciously agreed and we set out last Saturday morning on a new adventure.

I'll save the details of moving along the trail for another time. It is enough to say here, I think, that I made it by taking a few moments here and there along the way to catch my breath and rest aching muscles. And then, after short rest and relaxation once we reached the lake, an apple and some almonds, we made the hike back, almost 2,000 feet of de-elevation, rather quickly.

We talked a lot on the drive up and back, which is always a luxury in today's world of scheduled coffee meetings and planned "catch-up" time. On the trail, however, talk slowed. For one, I could barely walk and talk. For two, the beauty of the forest just past the prime of fall foliage was not to be missed by talking through it. And for three, silence is so rare in a city that the area's rich "silenceness" was like a third person traveling with us, needing my attention as much as the trail that stretched ahead.

Silence, of course, does not necessarily mean soundless. Our feet crunched over rocks and branches. Small streams of water creased the path now and again. The wind, fortunately mostly at bay this chilly day, swooshed quietly now and again. We ran into only seven other people over the hours we traversed Jennie's trail.

At the lake, I had to sit. "Vince the Photographer", always with an artist's eye, had portaged his camera. It was a relief to get off my legs, but I lost myself in the quiet silence of this drip of a lake, back dropped by snowy terrain and trees starkening as fall stripped their glorious leafy plumage. The elegant dark stubble of barren arbor-covered mountainside stood in contrast to the white undercoat beneath.

The quiet was interrupted only by shutters clicking, brief observations and replies, and then we had to go.

"I was falling in love with silence. Like most people with a new love, I became increasingly obsessed by it--wanting to know more, to go further, to understand better." ~Sara Maitland, A Book Of Silence, p. 33

Sara Maitland’s books, Silence and How to Be Alone, describe her journey toward solitude and silence. Using her own life as a “laboratory”, she sought silence in various venues, found she loved it, and eventually built a house in 2007 in a place where she could experience both silence and solitude as a way of life. Silence , published originally in 2008, is about these ventures and what she learned about silence along the way. How to Be Alone , published in 2014, sets out to more clearly differentiate between silence and solitude, and presents ways to find and enjoy being by oneself. Seeking to live a more peaceful, reverential life, with more planned solitude, I have referred to these books often.

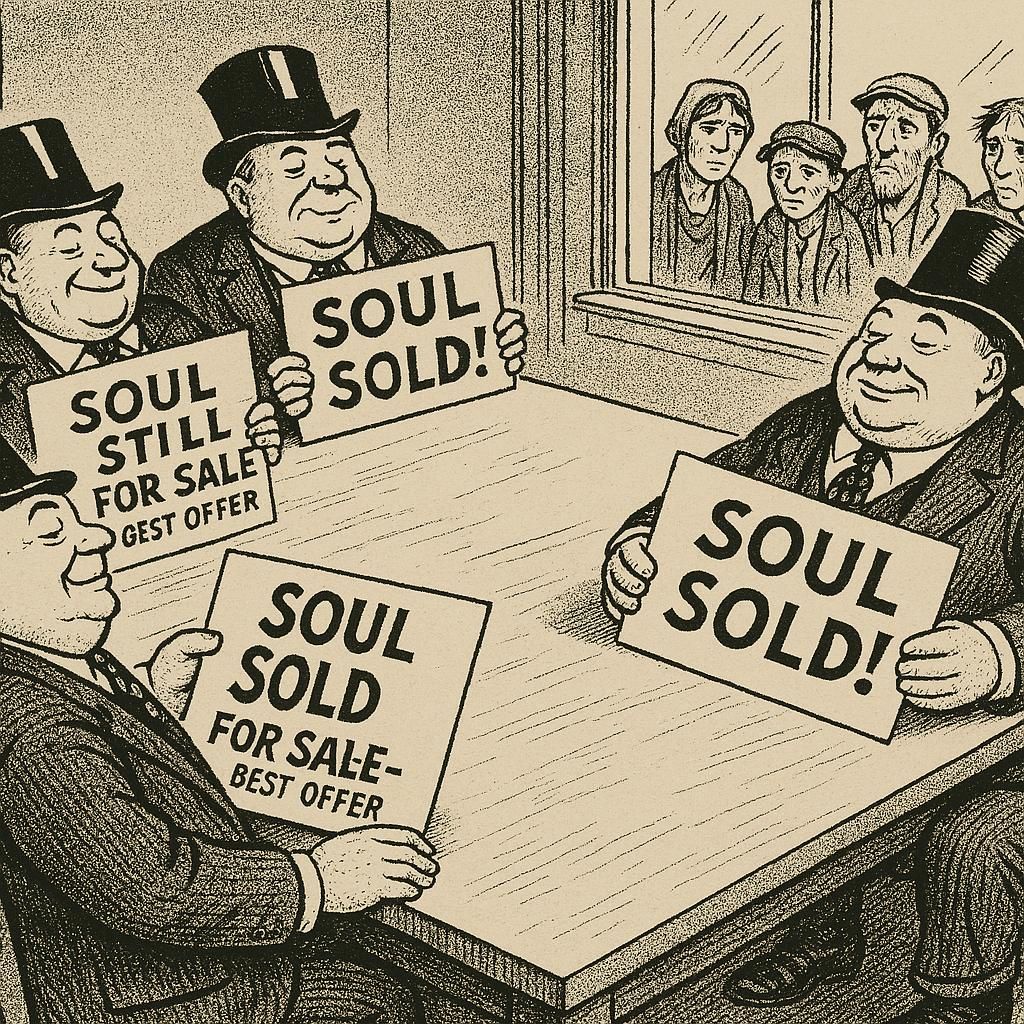

There is a qualitative difference, Maitland says, between silence which is voluntary and that which is imposed. “I now believe,” she says, “that the strongest determining factor in whether a silence ends up feeling positive or negative is whether or not it was freely chosen” (Silence, p. 92). She gives as an example marooning, that is, leaving someone alone on an isolated island. Pirates are most associated with this practice, which they invented in the early 18th century. They even included specific conditions for marooning in their ship’s articles. A firearm and shot, along with a bottle of water and a bottle of powder, were included in the deal so the marooned could kill him or herself rather than endure a lonely existence, an unalterable fate, and a slow death.

Imagine the difference between taking a solo camping trip to striking vistas in northern Idaho and being held prisoner, perhaps even being placed in solitary confinement? Even being marooned – left to die, without recourse, without hope –on a beautiful tropical isle would be a poor, hopeless substitute for a solitary fishing trip to an average stream or lake. Sensory deprivation, Maitland shows, can either be an experience at a spa, or torture. One is pleasure. The other? Imprisonment for those in solitary confinement might lead to “a terrifying sense that their individuality is disintegrating; a feeling that they are lost in the universe” (p. 91).

Alone or lonely. Silence or sensory deprivation. Solitude or isolation. Marooned or carried away to new adventures, new lands. Each person, each situation is different. One important variable – the freedom to choose one’s lot.

These days, silence seems a luxury. True silence, uninterrupted by humanly-created noise, is quite rare. Listening to instrumental music is humanly-created noise. Reading a book is humanly-created mind-noise. Listening to a squirrel chortle is not humanly-created noise. Unless there is a car running in the background.

Where do you find silence? Where is your Jennie Trail?

References:

Maitland, S. (2009). A book of silence.

Berkeley, Calif., Counterpoint: Distributed by Publishers Group West.

Maitland, S. (2014). How to be alone.

New York, Picador.