Open-mindedness and the Profound Learner

If one wants continually to go deeper into whatever area of life one is interested in, one must feel there is a deeper place to go to in the first place.

I hypothesize - to "assert" or, worse, to "pronounce" would undercut the entire idea I am proposing here - that open-mindedness is a quality of all profound learners. A profound learner, for our purposes, “is defined as a person who pursues deeper knowledge regularly over time” (Kroth, 2016, p. 29).

It would seem it must be so, right? For if one wants continually to go deeper into whatever area of life one is interested in, one must feel there is a deeper place to go to in the first place. To recognize there is more to know than one knows already is an assumption of open-mindedness. To believe one knows everything there is to know about this or that is to be closed-minded. Following this train of thought, to believe something is true is to be closed-minded about that "truth". The world is flat, for example, or hit songs of the 1950's and 1960's could never be a compelling part of advertisements created in 2021. Or...or...

To believe one has found the truth eliminates the motivation to search for truth.

Humility, and in particular, "intellectual humilty", suggests that none of us have complete knowledge. If we are interested in knowing more about the infinite amount of what we do not know, therefore, requires open-mindedness. Beliefs are important, in fact they are inevitable. But they should be considered, I have suggested, to be "resting places" on the journey to deeper assumptions about truth.

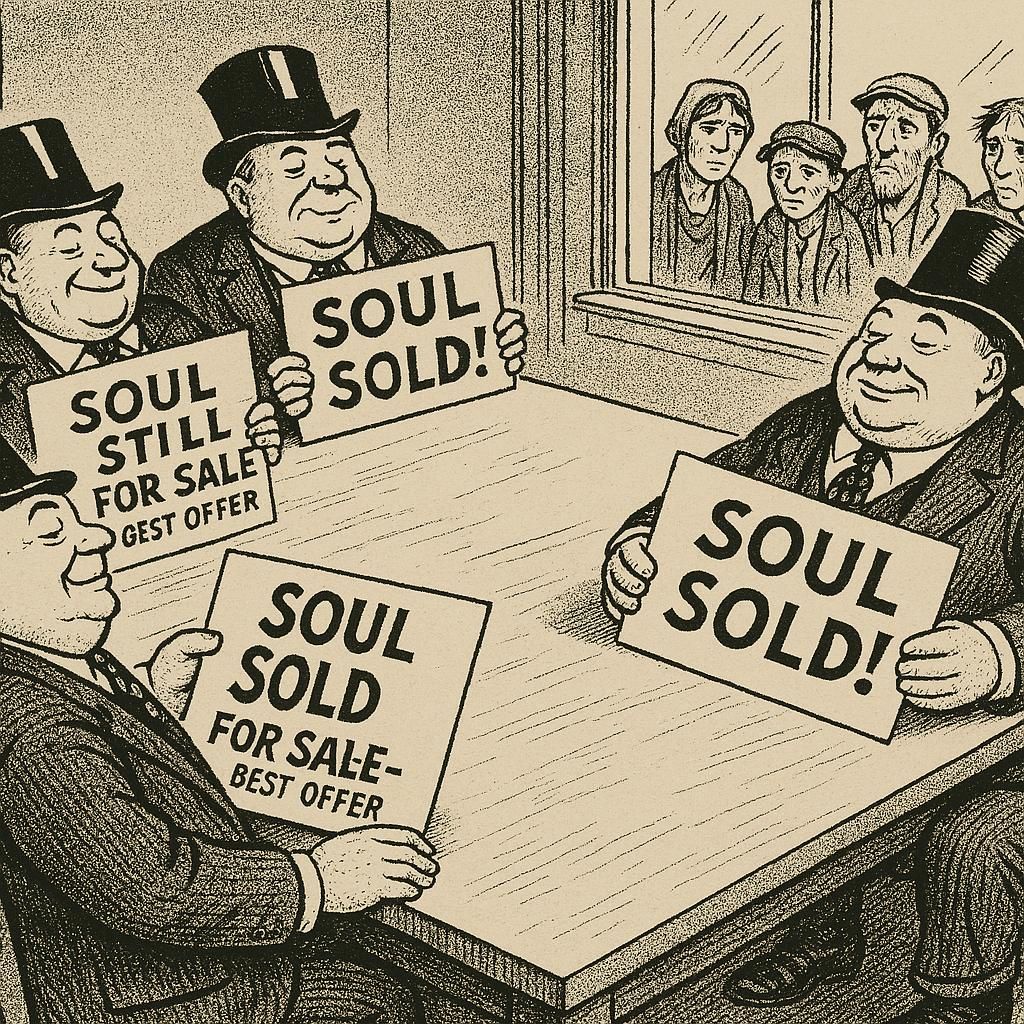

What has stymied so many, including myself of course, about this idea is the wishy-washiness aspect of open-mindedness. The relativity of open-mindedness makes it an easy target for those who have the power of certainty behind their opinions. “If you don’t believe anything to be true, then what do you stand for?”, goes the argument.

And it is a valid one.

Many of us have been subjected to bosses who change their management strategy every time they read the latest popular book or go to a conference. One hardly learns what the latest leadership "steps" are before the next "principles of" comes down the organizational elevator.

So...where do wisdom and intellectual thought and substantive knowledge and religious conviction and the pursuit of virtues and the idea of right and wrong fit into any desire to be open-minded?

Jason Baehr, in his book, The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology, has a chapter about open-mindedness which gave me a deeper understanding about this quality. I’m not a philosopher by trade or training, so I probably only “got” a small percentage of what he was saying, but here is what I see is the gist of his discussion.

He proposes different ways open-mindedness might be pursued:

1) a conflict model, in which there is a “a conflict between an open-minded person’s beliefs and some alternative belief or source of information” (p. 143). In this model, a person must be willing to temporarily suspend beliefs one has been committed to in order to fairly consider a different view or additional information. Open-mindedness in this situation is “the antidote to [intellectual] vices like narrow-mindedness, closed-mindedness, dogmatism, prejudice, and bias” (p. 144).

2) An adjudication model, in which the person has no particular view going in, and is simply looking at two or more sides as fairly as one can. Intellectual vices here which would inhibit a fair and thorough hearing of the sides of an issue, would be “traits like intellectual hastiness, impatience, and laziness” (p. 144).

3) An open-your-minds model [it is not clear to me if this is another ‘model’ or an ‘approach’ Baehr proposes] in which competing sides are not the concern but more like imagining a teacher asking students to “loosen your grip even more on some of your ordinary and commonsense ways of thinking about the world around you” (p. 146). This open-mindedness is dedicated to increasing understanding, and may involve taking in new information and then “to wrap their minds around it – to grasp it” (p. 146). Here, Baehr says, a person tries to figure out how the new information can be explained, and might involve creative thinking, imagination, or hypothesizing. It is “likely to require a kind of generative intellectual strength and autonomy” (p. 146).

The defining characteristic of all forms of open-mindedness, Baehr says, is that “In each case, a person departs from or detaches from, he or she moves beyond or transcends, a certain default or privileged cognitive standpoint” (pp. 148-149).

Intellectual virtues, Baehr says, are motivated by “a compelling or overriding desire to get to the truth” (p. 143). He defines open-mindedness as (p. 152):

An open-minded person is characteristically (a) willing and (within limits) able to (b) to transcend a default cognitive standpoint (c) in order to take up or take seriously the merits of (d) a distinct cognitive standpoint.

Note that this definition includes a person’s will and a person’s ability to transcend one’s own views and to consider different ones. A person, Baehr asserts, might be willing but, “simply cannot ‘think outside the box” and, therefore, doesn’t fit the definition of open-minded. Finally, while open-mindedness does not require that beliefs be adjusted if, say, the evidence is not persuasive, it does “necessarily involve adjusting one’s beliefs or confidence levels according to the outcome of this assessment” (p. 154).

In other words, being open-minded as considered here does not mean that one is wishy-washy, changing opinions based on the last book or speech or social media post one has heard or read, but it does require that when one does come across worthy new perspectives that they be incorporated into one’s overall worldview.

So, to be lifelong, profound learners we must - I suggest, or hypothesize - ask ourselves regularly if we are developing the 1) willingness and capability to 2) bracket - to take a timeout from - our own assumptions about “truth”, in order to 3) see if we can go more deeply into all that we do not yet, and will never ever be able to, fully know.

Finally, open-mindedness is “closely related to virtues like intellectual fairness, honesty, impartiality, empathy, patience, adaptability and autonomy” (p. 156); qualities like creativity are undergirded by it; and it “plays something of a facilitating role” for other virtues like intellectual fairness and honesty.

Baehr concludes his chapter by addressing the issue of when one should practice open-mindedness. He separates his discussion from moral reasons and focuses on the circumstances calling for intellectual virtue. His reasons all go back to the overall goal of intellectual virtue, that is, to reach ever toward truth.

The profound learner, as conceptualized here, is always seeking deeper knowledge about truth, recognizing that there is always more to know than can be known. And therefore, open-mindedness must be a quality of profound learners.

References

Baehr, J. (2011). The inquiring mind: On intellectual virtues and virtue epistemology. OUP Oxford.

Kroth, M. (2016).

The Profound Learner. Journal of Adult Education, 45(2), 28-32.