The Arrogance Of A Little Knowledge

My God Is Too Small

“By far the best way I know to engage the religious sensibilities, the sense of

awe, is to look up on a clear night. I believe that it is very difficult to

know who we are until we understand where and when we are.

”

(Sagan, 2006, p. 2)

Carl Sagan’s Gifford Lectures were compiled by Ann Druyan into the book, The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God (Sagan, 2006), the title of which is a “tip of the hat” (p. xv) to William James’ own 1901-1902 Gifford Lectures, later published as The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (James, 1997). The Gifford Lectures, which began in 1888 and have been given, with the exception of the war years 1942-45, to bring great thinkers – such as Hannah Arendt, Albert Schweitzer, and John Dewey, from fields as diverse as philosophy, science, and religion—to share their thoughts in the context of “natural theology”.

So what is natural theology?

"Traditionally natural theology is the term used for the attempt to prove the existence of God and divine purpose through observation of nature and the use of human reason...While for many people science and the scientific method seem to challenge the traditional understanding of faith, for others they complement their religious understanding." (See "Natural Theology").

That perspective, seeing faith, science, reason, religion-at-its-best, and spirituality as complementing each other, as informing each other, as profoundly deepening each other, is where I sit these days.

The topic of natural theology has engaged some of the most profound minds of our times. and for over 100 years the Gifford Lectures have provided a container where a good deal of the thinking about this has been spurred and also has found a home.

Early on in “The Varieties of Scientific Experience”, Sagan demonstrates that we live on a very small planet which exists in an unimaginably vast universe. Tiny earth is not in the center of the universe as we might imagine or wish. Instead, we are located in the backwaters, in the “galactic boondocks” (p. 24). Not only that, but Earth has existed for only a nano-blip of time, a micro-dot on the timeline since the universe jump-started with the Big Bang some 13.8 billion years ago and will become an ever smaller iota as the universe continues apace for billions and perhaps trillions of years after not only human existence but the planet itself is long gone. The point is, and everyone should know this well by now through personal experience, reason, and study, that in terms of time and space we are insignificant. In those terms we mean virtually nothing.

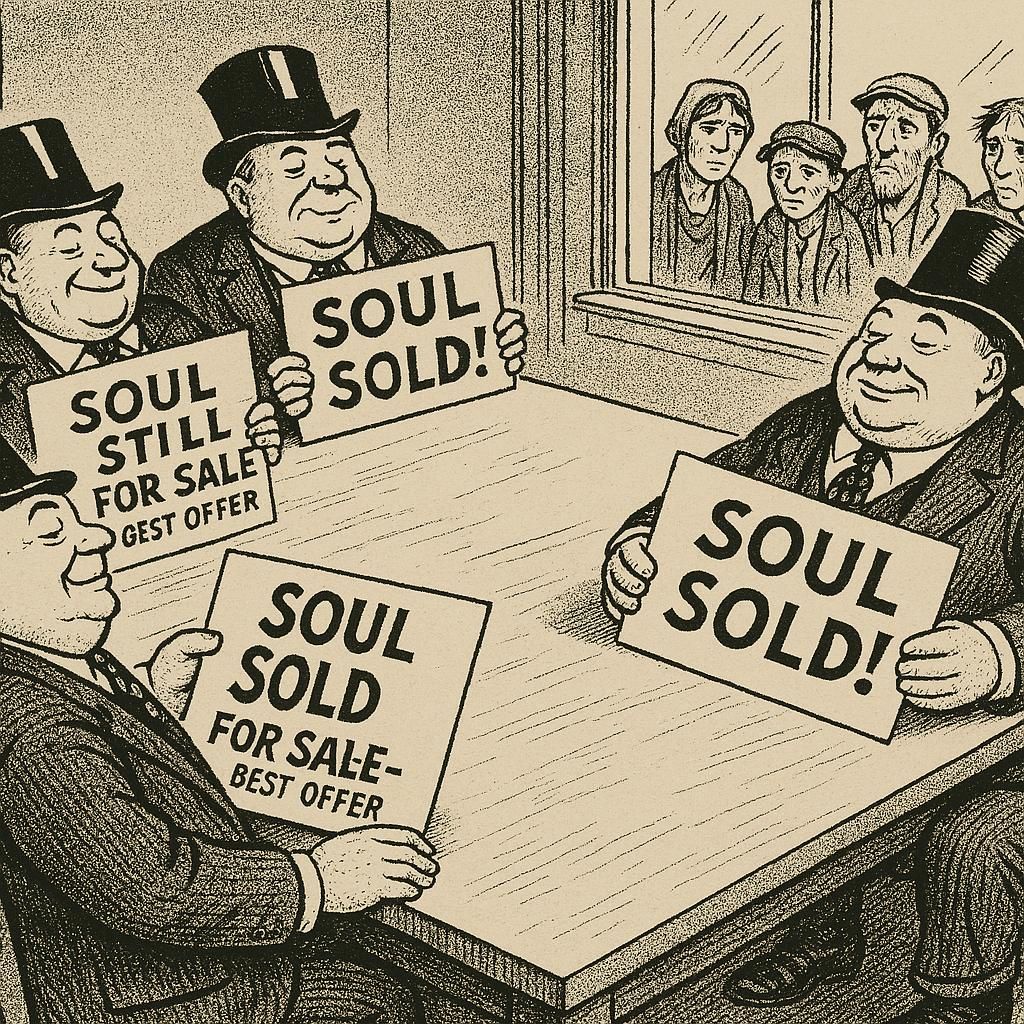

What struck me the most when reading this was what Sagan said about religion in this context. He said, “…a general problem with much of Western theology in my view is that the God portrayed is too small (emphasis added). It is a god of a tiny world and not a god of a galaxy, much less of a universe…it is a god of one small world, a problem, I believe, that theologians have not adequately addressed” (2006, p. 30).

God is portrayed as too small . When put in the context of time and space, the Bible and the Torah and the Quran were written for our little world, Earth, and it is entirely possible, perhaps probable, that they will be forgotten a billion years from now. How likely is it that there are million times the number of spiritual leaders and holy books existing in the universe right now? How likely is it that all those spiritual leaders and holy books of today and Earth's spiritual leaders and holy books of today will be long forgotten a billion years from now too?

Sagan says that humility is the “only just response in a confrontation with the universe, but not a humility that prevents us from seeking the nature of the universe we are admiring” (2006, p. 31). What deep reverence and awe and wonder bring are not answers, but questions. And seeking understanding is the purpose of both science and religion. Wonder is the motivator and eye-opener; mystery is the treasure we seek to comprehend.

Is there an Absolute? A God? The Divine? Is there some thing, some something, something...beyond my ability to ever know or experience or "grok"? Do I feel drawn to explore and to become closer every day to that mysterium tremendum ?

Yes. And Yes. And Yes. I feel moved to go more deeply and vastly and centeredly, to go more profoundly, more spiritually, more self-less-ly, more intimately each day and each moment. To be more totally present in that "divine milieu", as Huxley calls it, is my ongoing raison d'etre.

Yet...

...it is not a destination, not a place, that will be reached in my lifetime.

...it's a journey into an unknowable mystery, right? Every

time I have the audacity to think that I have a new idea, a contribution to

make to the body of knowledge, an insight to share, a depth I've uniquely experienced, I am easily and

embarrassingly disabused of that notion. This can occur in at least two ways.

The first is cognitive. I have only to open a book, say Barrow’s The Infinite Book

or Jennifer Michael

Hecht’s Doubt,

to see that what I

know, the amount of knowledge that I have, could fill one dimple of the tiniest

thimble in the land of Lilliput. The second is experiential. I have only to

walk into my back yard and look at the stars to feel the wonder of being a part

of something so beyond my ability to comprehend that makes me feel I am but a mite in a mighty

universe.

No matter how completely any human like myself experiences or imagines God, it can never be complete enough. Big enough. Long enough. We can but touch the mystery, the divine, can but immerse ourselves in the wonder of what surrounds and subsumes us. At our best, our notion of and experience of God and ability to explain God is smaller than God.

Still, in stillness, in aweful, awe-full, awe-full awe, there is that some some thing, that some thing, something...that we experience in union with that larger-than-life sacreditity we can't explain.

There will always be the need for those who get things done, who like a scientist or engineer bound a problem so that it can move toward resolution. There will be the need, always, for interpreters who edit what is known, so those of us on the path have guides. Too often those doers and interpreters misguidedly come to believe that what they think they know, what they espouse or have found to be a solution to a practical problem, is truth. They - that is, all of us - are wrong I think. At most, they/we have only partial truth. To recognize that is to take a step toward a humble spirit, a questioning instead of a defending, and thus a step further into the unknown.

References:

Barrow, J. D. (2005). The infinite book: a short guide to the boundless, timeless, and endless. New York, Pantheon Books.

"The Gifford Lectures: Over 100 years of lectures on natural theology." Retrieved 7-12-15, from http://www.giffordlectures.org/.

"Natural Theology" https://www.giffordlectures.org/overview/natural-theology , Retrieved 10-26-18

Hecht, J. M. (2003). Doubt: a history: the great doubters and their legacy of innovation, from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson. United States of America, HarperSanFrancisco.

James, W. (1997). Varieties of Religious Experience. New York, NY, Touchstone.

Sagan, C. (2006). The varieties of scientific experience: a personal view of the search for God . New York, Penguin Press.