The Beatitudes Are A Call To Arms

“The poor in spirit are by no means poor-spirited. They are persons who see so much to be, so much to do, such limitless reaches to life and goodness that they are profoundly conscious of their insufficiency and incompleteness.”

~Rufus Jones, The Inner Life, p. 19

Note: This essay, here with a few edits, was first delivered as a reflection for the Cathedral of the Rockies Candlelight Service on January 27, 2025. You can watch a video of the reflection here.

The Beatitudes are a call to arms. But this call to arms is not saber rattling, it isn’t uppercuts or clenched fists. It isn’t making a show of force with innocent people, with people who disagree with you or protest against you. It isn’t the arms of guns or pepper spray or bullets or masks.

No, this call to arms, these Beatitudes, these Christian dispositions and actions, are a call for arms that embrace. That support. That love. That sacrifice. That protect. That are warm and soft and strong.

I am making the case today that the contemplative life, contemplative practices, prepare us for open arms – for receiving them and for sharing them.

Embracing arms.

Let’s remember the Beatitudes, spoken by Jesus.

The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1–12, KJV)

1 And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him:

2 And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

3 Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4 Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

5 Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

6 Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

7 Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

8 Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

9 Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

10 Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

11 Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

12 Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

What are we called to embrace?

What are we to make of this sermon, this call? The profound Quaker author, Rufus Jones, writing about the “blessed-ness” described in the Beatitudes, said

“It is not a prize held out or promised as a final reward for a certain kind of conduct; it attaches by the inherent nature of things to a type of life, as light attaches to a luminous body, as motion attaches to a spinning top, as gravitation attaches to every particle of matter. To be this kind of person is to be living the happy, blessed life, whatever the outward conditions may be.”

“The beatitude attaches…to hunger and thirst for goodness.’

"The beatitude attaches…to hunger and thirst for goodness."

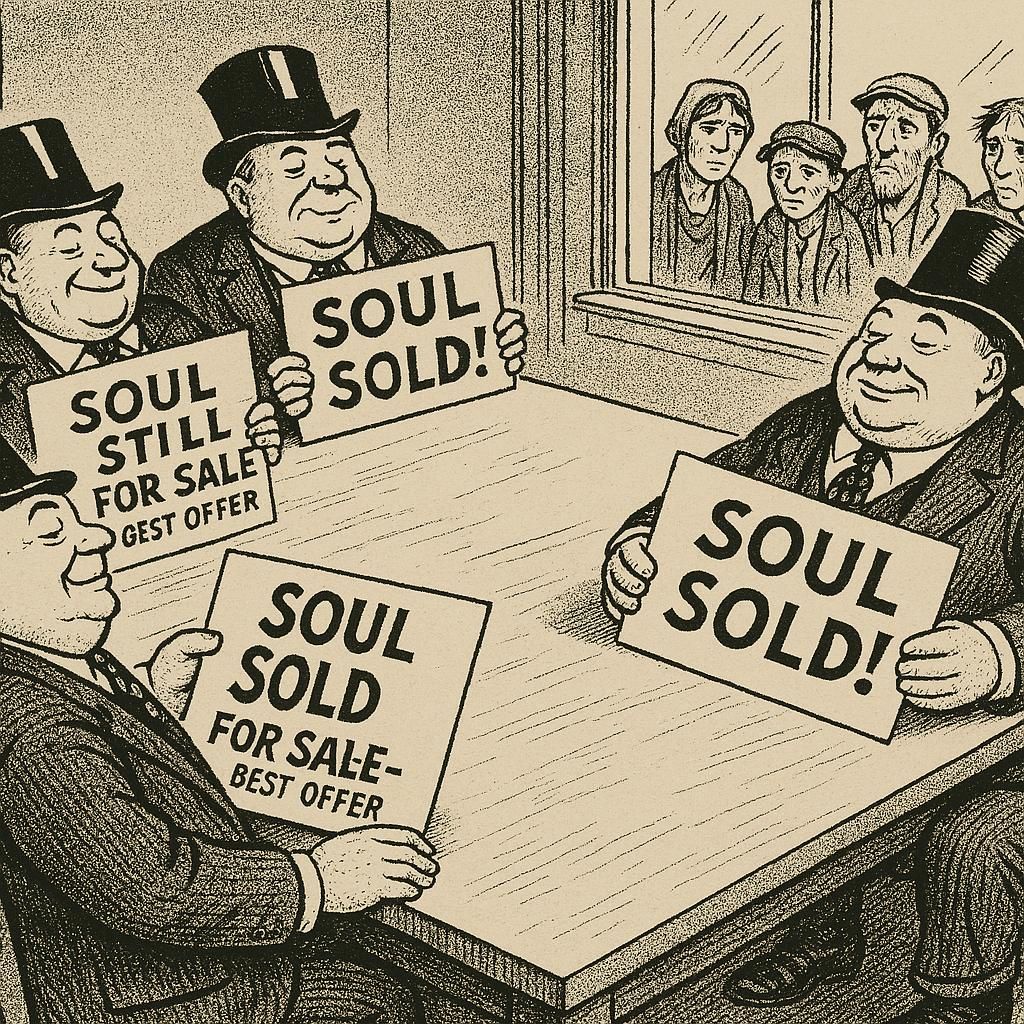

These are words of humility and sacrifice, not of domination or control.

The beatitudes are not just telling us what kind of people we should be, but also who we need to lift up, to cherish, and what we need to do. The Beatitudes give us the road map.

Jesus says those who are poor in spirit, who mourn, who are meek, who are peacemakers, who are pure in heart, who thirst for righteousness, who are merciful, and who are persecuted and insulted and lied about because they follow Him – will be comforted, inherit the Earth, will be shown mercy, be satisfied, called the Sons of God – theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

Those qualities are the arms of embrace. They are the acts of loving God with all one’s heart, mind, soul, and body and one’s neighbor as oneself.

Contemplation and the Beatitudes

And let’s not forget that contemplation and the Beatitudes complement each other. What we do in contemplation – through intentional practices of silence, stillness, prayer, singing, and worship – to is experience the presence of the divine. To hear the divine call. To experience the mystery. If we practice, and we listen, then we are formed, often so slowly, into people following the ways of mercy, humility, peacemaking, courage, and sacrifice.

Foundational to this formation is experiencing the “sacrament of the present moment,” as de Caussade wrote, or as T.S. Eliot expressed in Burnt Norton:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor

fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance

is

What is the still point, what is the dance?

Moving Stillness

I think of contemplation, engaged in opening the arms of the world, as Moving Stillness. Moving with peace and courage and resilience and hope through a troubled world. Stepping into the chaos of politics, warring parties, inequity, and a myriad of other troubles with a profound depth of spirit. That’s the dance of contemplative stillness.

“A talent forms itself in solitude,” Goethe wrote, “A character amid the stream of life.”

This contemplative work begs the question, “How might I intentionally become closer to God; how might I become a more humble, merciful, peacemaker? How can I practice the disciplines in order to embody moving stillness?

Contemplation opens our arms to others, to embrace a world that needs to be surrounded in love.

Sources

Caussade, J. P. d. (1982). The sacrament of the present moment. Harper & Row.

Eliot, T. S. (1963). Burnt Norton, in Collected poems, 1909-1962 (1st American ed.). Harcourt. p. 177.

Goethe, J. W. von. (1993). Torquato Tasso (C. E. Passage, Trans.). In F. G. Ryder (Ed.), Plays (p. 155). The Continuum Publishing Company. (Original work published 1790).

Jones, R. M. (1917).

The inner life. The Macmillan company. From pages 16, 17, 18.