The Imitation Of Christ VI

Temptation

Author's Note: This essay series, The Imitation of Christ , has been prompted by Thomas a Kempis' book of the same name. I am particularly interested in exploring these topics because of a project my friend, colleague, and co-author, Bryan Taylor, and I are working on, using The Imitation of Christas its foundation.

These are vast and deep topics and, as with most of my writing, I learn more and more about what I think and know, and about what I think I think I know, and understand about them, by writing about them. Readers are likely to have additional or differing insights on these themes, and I invite you to join the Profound Living Page and Group on Facebook if you have thoughts or ideas to contribute to any of them.

“As long as we live in the world we will always face troubles and trials…

People are never so perfect in holiness that they never have temptation,

nor can they be completely free from them.”

~à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, p. 217)

A temptation is something which tests you, which tests your volition, which tests what you or others have established as the way you should proceed.

If temptation is considered a test of our pre-set intentions, then passing or failing these tests may be large or small in consequence. I might choose to forgo something – alcohol, chocolate, sodas – for, say, Lent. During that period, those renunciations could be considered temptations, or tests of my will. The outcome of succumbing to these self-imposed and time-specific temptations is likely to be relatively minor. If I choose not to be a felon, however, then succumbing to the temptation of stealing money by robbing banks is likely to result in a more consequential result.

It is important to note that what was not considered a temptation before the intent was set, became something deemed a temptation afterwards. That suggests that temptation is subjective and variable. Some tests are imposed on us by others – significant others, social standards, culture, religion – which we may not have chosen for ourselves. Some tests we impose upon ourselves. These we freely or at least intentionally decide we wish to take on. These two – the tests others impose and the tests we impose on ourselves – are intermingled. Our individual intent has been formed by what has surrounded us and influenced us since birth.

Nonetheless, there are times when others test what we would not, and there are times we set tests for ourselves in ways others might not expect of us.

What qualifies as a temptation depends on who or what is setting that test before us. In one culture, what is defined as a temptation might be acceptable behavior in another. In one setting, the wine tasters club, what is defined as a temptation might be different than what it might be in a temperance group. In one setting, an Olympic training facility, what is defined as a temptation might be different than what it might be in a writing retreat. People even within one religious denomination might define temptation differently, or differently over time. When I was growing up, abstinence seemed a clear standard and alcohol a clear temptation in our church. These days those expectations I believe are different and therefore so are the associated temptations.

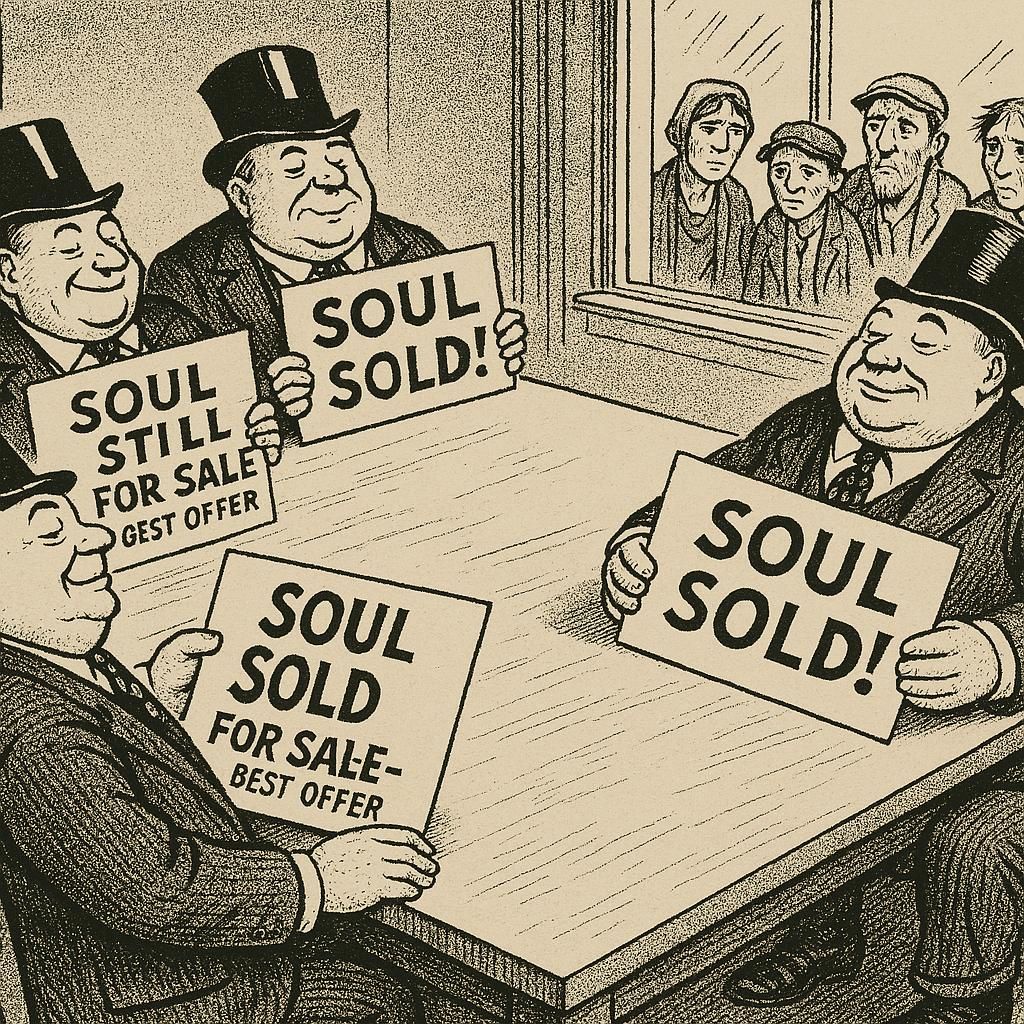

Temptation, therefore, is part of a larger template of what is considered right or wrong. That varies widely. A person might be considered as surrendering to temptation by one group, but their own group does not consider it a transgression at all. The opportunities for judging others are plentiful, are they not? Until, and in the unlikely event, all groups and people agree upon what constitutes right or wrong, people will never be able to overcome the temptation seen in some other’s eyes.

The opportunities for judging others are plentiful, are they not?

How might an an individual approach the challenge of temptation? First, the person must have a clear idea of what they expect of themselves. As mentioned before, those expectations may come from different sources. The more these expectations fit into the person’s sense of right and wrong and good-for or bad-for behaviors, the less internal combat will take place when faced with temptation, say that chocolate bar. Discerning what one considers, or should consider, right and wrong or good or bad in the first place is thus a key to success.

However, even with steadiness and unity of purpose, the tests of temptation will still arise. And that is because desires are built into us as a biological, meaning-making species.

Which brings us to the virtue of temperance. Temperance has a different root, the Latin temperantia , which means "self-control, moderation, restraint", than temptation’s Latin root, temptāre , tentāre which means "to feel, test, examine, attempt, make an assault on, attack". Because, as à Kempis writes, ““We are never completely free from temptation for as long as we live…”, developing the virtue of moderation seems essential. As Stanley Hauerwas points out, “In fact, the problem with the presumption that our passions must be subject to our control is that it usually leads to the unfortunate outcome that our desires control us”.

If it is desire that tempts us, then the virtue of temperance may help us to self-regulate our response to desire. Desires are not inherently bad. As Hauerwas says:

"Temperance is the virtue made necessary by the fact that our lives are constituted by desire. It’s easy to miss this fact because we find it hard to acknowledge what makes us who we are—it’s so close to us that we can fail to comprehend what really makes us tick. For instance, we seldom notice that we want to live because that’s a constant, fundamental desire."

We also seldom notice how the most basic things we do reflect our desire to live. Eating is one of those things, and it’s often been seen as one of the aspects of our lives that should manifest temperance…A temperate person must take pleasure and enjoyment in eating the right things rightly.

Desire permeates our lives, that’s how we are able to live. Virtue, as Hauerwas suggests here, is doing the right things rightly . That, of course, makes this whole endeavor subjective once more as people will differently define what is "right" and what is "rightly".

There are those, of course, who will do that for us. That is why we have laws, doctrines, unwritten and written social standards, received knowledge from wise others – which we either buy into, or do not accept. Right and wrong, and ethics and morality, are all involved and are subjects too vast and deep for this essay.

These are not easy matters.

Unless…..

Unless, we spend the time necessary to develop what we consider "good" practices regularly, to see through trial and error what works for us, to examine and re-examine our commitments to this or that belief system and why it is important to us or why we are just going along with it, and over time to develop a sense what is profoundly and crucially meaningful for us, so that we can set our own goals and standards and expectations which we can then test ourselves against .

From a spiritual perspective, Fenelon says:

“I know of only two resources against temptations. One is faithfully to follow the interior light, instantly and immediately cutting off everything that we are at liberty to dismiss that may excite or strengthen temptation…The other resource against temptation consists in turning to God whenever temptation comes…”.

If that's true, feeding that interior light is essential. Your development strategy may then be to spend time and energy on what glows within you, to eschew that which would dim the light. Your constant approach would be to look often, perhaps constantly, to discern what is profoundly meaningful to you for guidance. Your ongoing practices would be to develop the skills, knowledge, behaviors, and attributes over a lifetime that allow you to act accordingly.

In that way temptation would ever more be supplanted by the desire to do what is right, and thus result in more desirable outcomes over time.

Along that path, the tests are ones of daily practice which lead to desirable outcomes. Building the will comes from discipline. Daily practices - of, say, generosity, gratitude, service, study, and contemplation - exercise the mind, body, heart, and soul. In that way, the cycle of growth in this context might look like: Temptation (desire), Contemplation (rewire), Creation (inspire). Or Purpose, Practices, Performance.

Along the way, we are bound to fail time and time again. Rather than letting those failures defeat us, these setbacks can and should be instructive. As à Kempis writes,

“…temptations can turn into great benefits. Through them we are humbled, purified, and instructed. All saints have endured many troubles and trial and temptation, yet have grown through them. Those who have not endured temptation become good for nothing and fall away. There is no state so sacred, no place so secure that it is without temptation and troubles” .

References

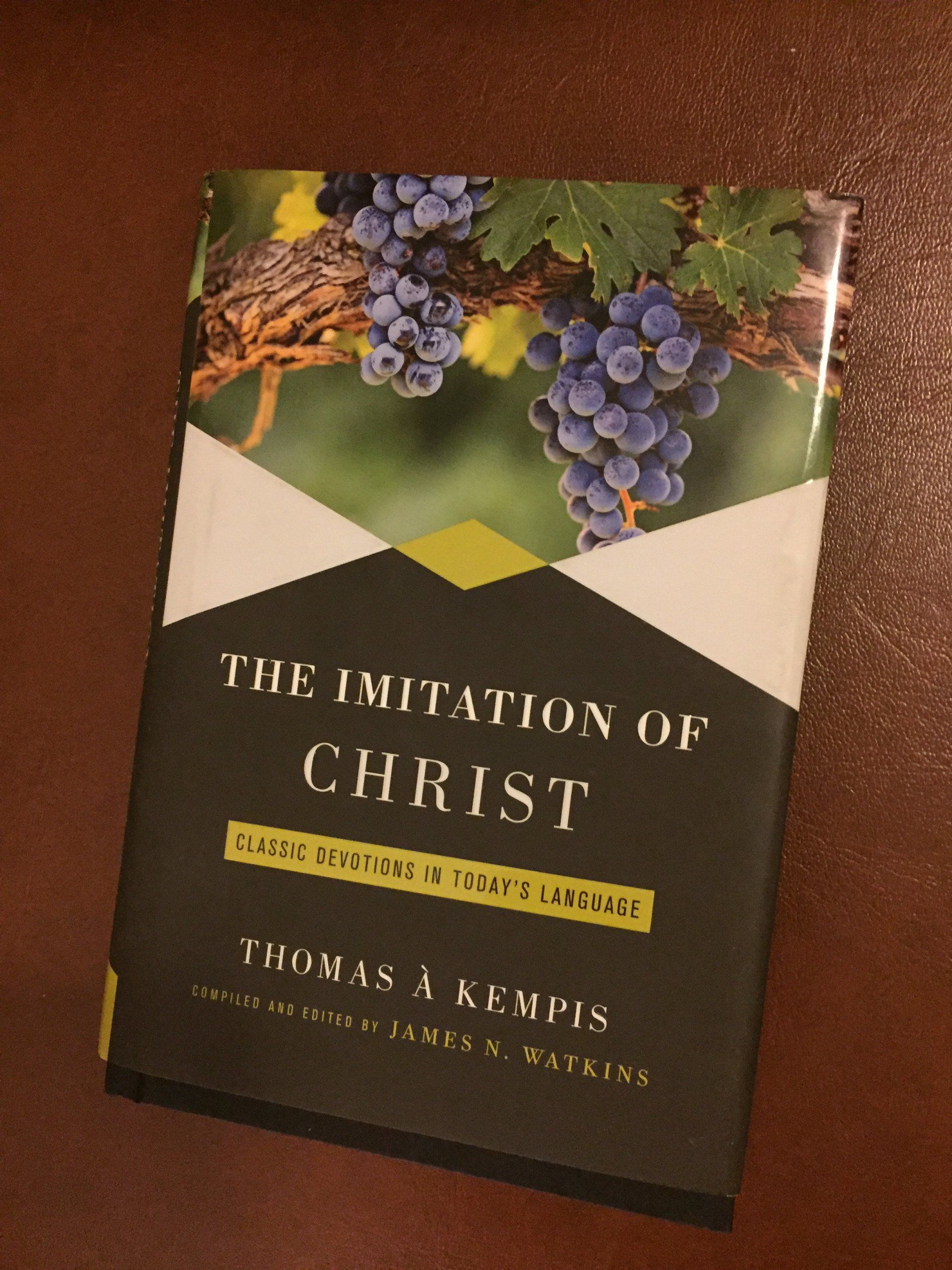

à Kempis, T. (2015). The imitation of Christ: classic devotions in today's language (J. Watkins, Ed.). Worthy Inspired, an imprint of Worthy Publishing Group.

Fénelon, F. o. d. S. d. L. M. (2008).

The complete Fénelon

(R. J. Edmonson & H. M. Helms, Ed. & Trans.). Paraclete Press. Table of contents only http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0818/2008021654.html

Hauerwas, S. (2018). The character of virtue: letters to a godson . William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Temperance. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 14, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/temperance

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Tempt . In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 13, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tempt

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Temptation. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 13, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/temptation

Photo Credit

Photo by Michael Kroth