The Imitation of Christ VIII - Virtue Development

The Practice of Virtuous Living

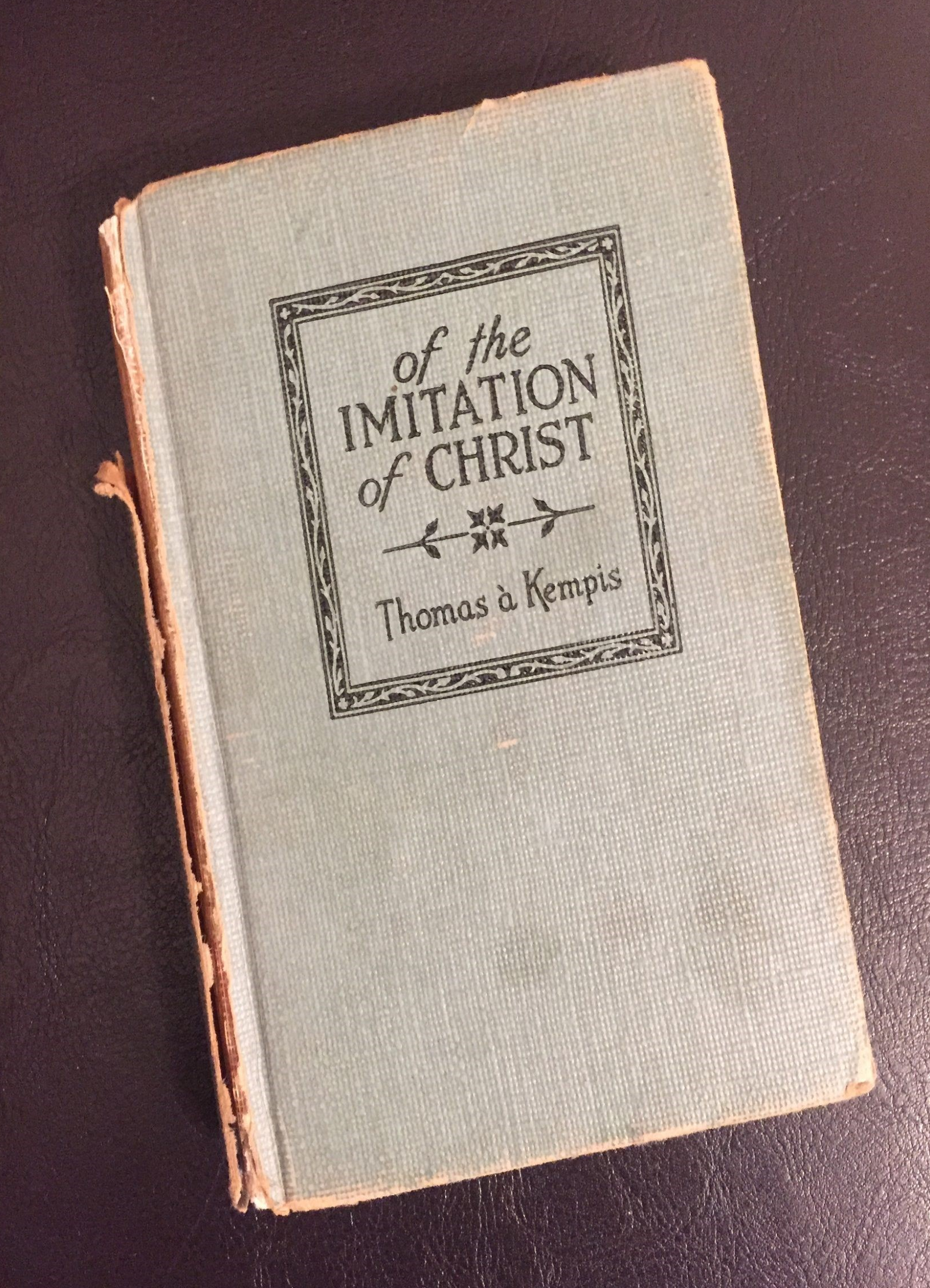

Author's Note: This essay series, The Imitation of Christ, has been prompted by Thomas à Kempis' book of the same name. I am particularly interested in exploring these practices because of a book my friend, colleague, and co-author, Bryan Taylor, and I are working on, using The Imitation of Christ as its foundation.

These are vast and deep subjects and, as with most of my writing, I learn more and more about what I think and know, and about what I think I think I know, what I don’t know, and what I understand about them, I think, by writing about them. Readers are likely to have additional or differing insights on these themes, and I invite you to join the Profound Living or Practices for Deeper Living groups, and/or the Profound Living page on Facebook if you have thoughts or ideas to contribute to any of these topics.

The Imitation of Christ, my first copy, purchased used at the Mt. Angel Library. Photo by me.

“Most of us have clearer strategies for how to achieve career success than we do for how to develop a profound character.”

~David Brooks, The Road to Character, p. xii

Until the last few years, I knew almost nothing about virtues, and even less about virtue development. Now, virtue development is becoming more and more integral to the scholarly work we are engaged in, my own personal inquiry and, most importantly to me, my life. To say that the history, qualities, and day-to-day application of virtue was scantily emphasized as I grew up, went to church, and studied in school, would be over-generous.

I can say accurately that in my Methodist family home, even when including my church-going, “Old Rugged Cross”, grandparents, the word virtue was so seldom used that I don’t remember it once. In those days there wasn’t even “Character Counts” in school.

And yet, looking back on what it was like growing up in Kansas, the practice of living with virtue, positive values, and character was an essential and integral part of life. I even wrote song lyrics about it.

When I was growing up in Kansas my grandpa said to me,

Michael in our family we do not call folks’ names,

We never put out little half-truths just to win the game,

The Golden Rule’s our motto, because you must see,

In rural Kansas of the 60’s, character is king.

~Michael Kroth, Where Have Small Town Values Gone

(you can read the whole song and discussion about it here.

In those days, I learned virtues and values by observation and by being told what was important. My grandfather gave up a promising career in education to return from Michigan to manage the family farm in Kansas when my great grandfather died. (Family. Sacrifice. Caring for others.) I watched my grandparents conserve every resource they had from clothes to farmland, repurposing whatever they could until it fell apart before letting it go (they didn’t have recycling bins in those days, but then again, they didn’t have one-use plastic bottles either). (Frugality. Durability. Sustainability.) I saw neighbors helping each other every day and jumping in with both feet when someone was in trouble. (Neighborliness. Generosity. Relationships.)

Those were strong, character-building times, and yet, as David Brooks keenly notes, they were not perfect.

“The research [Brooks was doing] reminded me first of all that none of us should ever wish to go back to the culture of the mid-twentieth century. It was a more racist, sexist, and anti-Semitic culture. Most of us would not have had the opportunities we enjoy if we had lived back then….in so many ways, life is better now than it was then."

But, he goes on to say, “it did occur to me that there was perhaps a strain of humility that was more common then than now, that there was a moral ecology, stretching back centuries but less prominent now, encouraging people to be more skeptical of their desires, more aware of their own weaknesses, more intent in combatting the flaws in their own natures, and turning their weaknesses into strength.”

“There was stronger social sanction against (as they would have put it) blowing your own horn, getting above yourself, being too big for your britches” (p. 5).

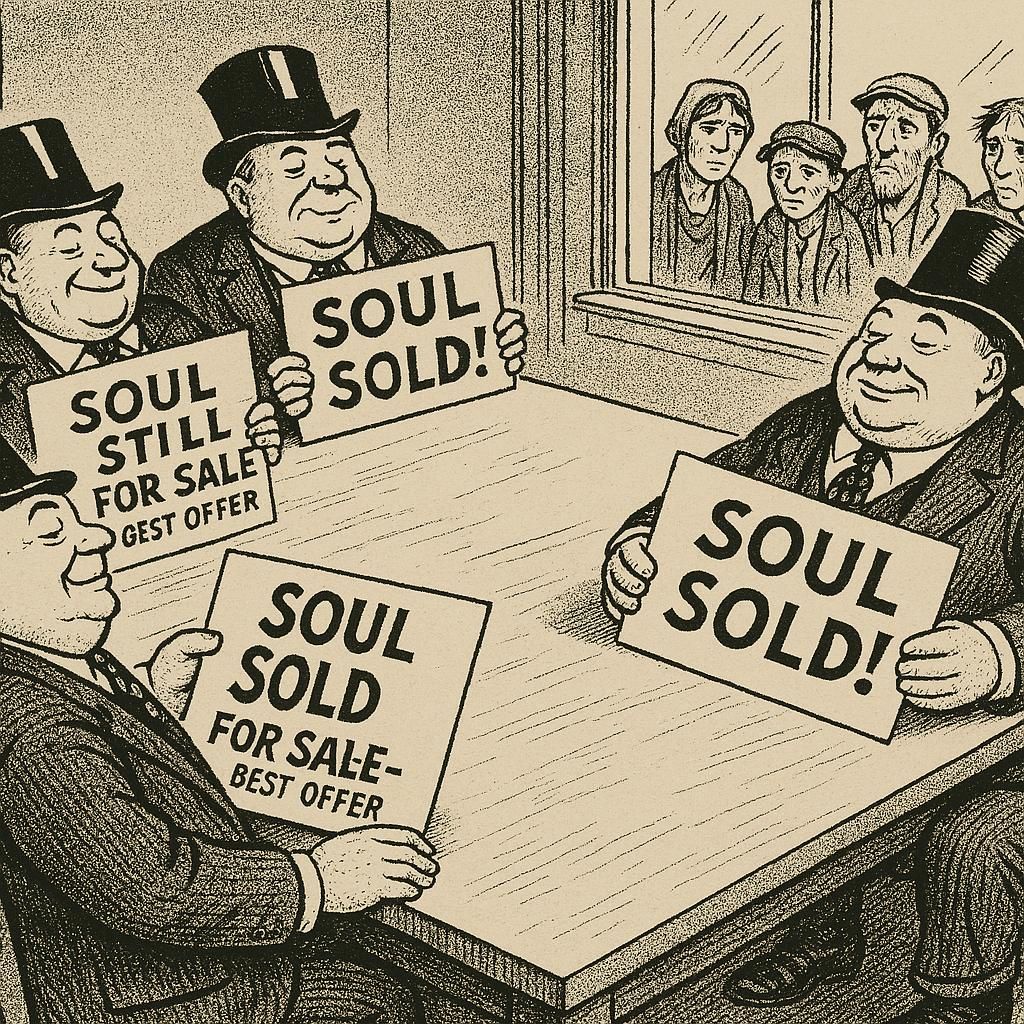

It seems to me that virtues and virtue development, especially in times like these when virtues like honesty, fair play, and the Golden Rule seem to have been lost in the socio-politico-techno busyness of getting ahead and winning, need to become, once again, a top priority.

I’m at the very beginning of understanding intellectually what virtues are and have been historically and, more importantly, what it takes to develop them in spirit and in practice. Here are a few pieces I’m starting to put together. The first is that virtues come in a variety of forms.

Types of Virtue

First, a basic definition of virtue (from Virtue Ethics, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) is:

”A virtue is an excellent trait of character. It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor—something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker—to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways."

Further,

“The concept of a virtue is the concept of something that makes its possessor good: a virtuous person is a morally good, excellent or admirable person who acts and feels as she should.”

Aristotle (1951) said there were two types of virtue, moral and intellectual, and that “intellectual excellence owes its birth and its growth mainly to teaching” (p. 181), requiring experience and time, and moral excellence is “the product of habit”, and therefore none of them are “implanted in us by nature” (p. 181). Hence, “nature gives us the capacity for receiving [virtues], and this capacity is developed through habit (italics added)” (p. 181).

Intellectual virtues are one broad category. Phillip Dow (2013) identified seven: Intellectual Courage, Intellectual Carefulness, Intellectual Tenacity, Intellectual Fair-mindedness, Intellectual Curiosity, Intellectual Honesty, and Intellectual Humility. These influence, he says, our lives just as moral character does. Intellectual character deals with the thinking habits needed to find and apply knowledge. It is “the forces of accumulated thinking habits that shape and color every decision we make” (p. 22). These are not light-weight virtues. Jason Baehr, speaking of intellectual character, said “a fully or broadly virtuous person can also be counted on to care deeply about ends like truth, knowledge, evidence, rationality, and understanding; and out of this fundamental concern will emerge other traits like inquisitiveness, attentiveness, carefulness and thoroughness in inquiry, fair-mindedness, open-mindedness, and intellectual patience, honesty, courage, humility, and rigor” (p. 2).

In the Catholic Church, the four Cardinal Virtues are prudence, justice, temperance, and courage (or fortitude) and the three Theological Virtues are faith, hope, and charity. The Catechism of the Catholic Church describes a virtue “as a habitual and firm disposition to do the good. It allows the person not only to perform good acts, but to give the best of himself. The virtuous person tends toward the good with all his sensory and spiritual powers; he pursues the good and chooses it in concrete actions. The goal of a virtuous life is to become like God” (p. 495).

The United Methodist Church, where I hang my religious hat, it turns out doesn’t think much about virtues at all. I searched our website, but there was almost nothing I could find about virtues, so I sent a note to “Ask the UMC” to see what gave. I got a quick response, which said:

“Talk of ‘the virtues’ is not really part of Methodist vocabulary. This is more a product of Catholic and some Orthodox teaching.

What you will find in the preaching of John Wesley, though not within the sermons included in the doctrinal standards, is some attention to what we might now call ‘the fruit of the Spirit’ and what John Wesley (and a good bit of Anglican devotional literature before him) refer to as ‘holy tempers’”.

Holy Tempers. Holy Tempers.

In all my years as a Methodist, it’s hard to remember times when Holy Tempers have been discussed, though my memory isn’t as good as it once was. Suffice it to say, they haven’t been emphasized prominently as something integral to lifelong spiritual formation.

I will have to come back one day and delve more into Holy Tempers and their relationship to virtues. Wesley scholars like Randy L. Maddox (2005) have discussed them and their relationship to what Wesley called the virtuous heart and the virtuous life. He analogizes Wesley’s view of tempers as “tempered steel” (p. 28) such that they have become enduring dispositions which have been developed and strengthened. That holds promise - I'm interested.

Virtue and The Imitation of Christ

Finally, and back to what birthed this essay, comes à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, and his emphasis on virtue. In the very first Chapter of Book I, he writes,

“Surely great words do not make a man holy and just; but a virtuous life maketh him dear to God.”

In Book I, Chapter III, he says,

A humble knowledge of thyself is a surer way to God than a deep search after learning. Yet learning is not to be blamed, nor the mere knowledge of anything whatsoever, for that is good in itself, and ordained by God; but a good conscience and a virtuous life are always to be preferred before it.”

And in Chapter XXV, Book I, “Without care and diligence thou shalt never get virtue.”

When I first read this “how-to” book, I was struck by the emphasis on what to do, instead of simply what to believe. Live virtuously, says à Kempis, and the book is filled with ways to do that – to think humbly of ourselves, resist temptation, avoid rash judgment, live in truth and humility, be charitable, and resist pride, as examples. He placed much emphasis on living a good, simple, virtuous life. Writing as a Catholic, and for Catholics (indeed, this was written before the Protestant Reformation), The Imitation of Christ became the most important Catholic devotional book and, after the Bible, the most read devotional book. Practicing virtuous living is an essential part of what this book has to say.

Imitating Christ means imitating Him. Practicing, on a day-to-day basis, the virtues he exemplified. Walking the talk. Step-by-step. Camino after camino.

Resources/Sources

Aristotle. (1951). Aristotle: Containing Selections from Seven of the Most Important Books of Aristotle... Natural Science, the Metaphysics, Zoology, Psychology, the Nicomachean Ethics, On Statecraft, and the Art of Poetry. Odyssey Press.

Baehr, J. (2011). The inquiring mind: On intellectual virtues and virtue epistemology. OUP Oxford.

Brooks, D. (2015). The road to character (First edition. ed.). Random House.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. (1997). (2nd ed.). Doubleday.

Dow, P. (2013). Virtuous minds: intellectual character development for students, educators, & parents. InterVarsity Press.

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, "Virtue Ethics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/ethics-virtue/>.

Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, The John C. Winston Co.

Maddox, R. L. (2005). Shaping the Virtuous Heart: The Abiding Mission of the Wesleys.” Circuit Rider, 29(4), 27-28.

The Imitation of Christ (Wikipedia), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imitation_of_Christ

Willard, D. (1990). The spirit of the disciplines: understanding how God changes lives. HarperSanFrancisco.

More thoughts about virtues:

“Recently I’ve been thinking about the difference between résumé virtues and the eulogy virtues. The résumé virtues are the ones you list on your résumé, the skills that you bring to the job market and that contribute to external success. The eulogy virtues are deeper. They’re the virtues that get talked about at your funeral, the ones that exist at the core of your being—whether you are kind, brave, honest or faithful; what kind of relationships you formed” (Brooks, 2015, p. xi).

“…individual intellectual virtues tend to ‘flow’ from something like a desire for truth or knowledge…” (Baehr, 2011, p. 6).

“Your intellectual character consists of your inner attitudes and dispositions toward things like truth, knowledge, and understanding” (Dow, 2013, p. 11).

“My central aim is that we can become like Christ by doing one thing—by following him in the overall style of life he chose for himself.” (Dallas Willard, p. ix)

Other Essays in The Imitation of Christ Series

The Imitation of Christ - Practices for Daily Living

The Imitation of Christ I - Was I Serious About Living A More Meaningful Life?

The Imitation of Christ III - It Would Take A Lifetime Just to Get This Starting Chapter Right

The Imitation of Christ IV - Examine Your Conscience

The Imitation of Christ V - Embracing the Sacraments

The Imitation of Christ VI - Temptation

The Imitation of Christ VII - The Practice of Prayer